I’m Vaughn Tan, and this is another of my weekly attempts to make sense of the state of not-knowing. The first issue explains the project; you can see all the issues here.

My first book, The Uncertainty Mindset, is now out. It’s a behind-the-scenes look at cutting-edge high-end cuisine … and what it can teach us about designing better organizations. You can get it here. If you like it, help me out by leaving a review somewhere.

Book events are coming soon! Tell me what you’d like to see and sign up for notifications here.

Hello friends,

This week’s issue is about publishing uncertainty, and it is long.

tl;dr—there might be something interesting to be done in publishing by:

Focusing a new business on the higher-uncertainty parts of the conventional publishing value proposition: a) finding authors; b) developing embryonic content into monetizable product; c) producing normally unviable content,

Reducing the cost of the lower-uncertainty parts of the conventional publishing value proposition—like production and distribution—by using non-legacy workflows and processes,

Concentrating on finding and developing book content that appeals to diverse and fragmented audiences,

Exploring both traditional and non-traditional formats for releasing said content,

Developing book content and marketing through aggressively monetization intermediate work product,

Building book-level business models around the expectation of monetizing both intermediate and final work product.

For the back story, read on.

In March, I was added to a WhatsApp group for non-fake coronavirus news which got serious and stern too quickly. But a splinter group soon formed that was more enjoyable because the messages of deepening doom there are leavened with dog photos, emoji, and discussions of machine-learning enabled video analysis. I met James on this splinter group. He’s a VC at Bloomberg Beta and, for reasons I can’t fathom but am very pleased by, he appears to like my book. Especially the bits that describe food.

He and I got to talking on a combination of Twitter DMs and WhatsApp messages about why my book was so illegible and undiscoverable to people who might otherwise enjoy reading it. (He only picked it up on Kindle when he noticed that I’d changed my Twitter handle to announce the book’s availability.)

Through a mix of WhatsApp messages, public tweets, and Twitter DMs, he set up a call with David King, Highlighter’s founder, to talk about publishing. I came at it from the perspective of someone who

Has just (somehow) managed to get a book out which is uncategorizable,

Has been through academic book and journal publishing vicissitudes,

Enjoys uncategorizable and illegible stuff, and

Has been thinking practically about alternative publishing (with Josh Berson).

It was an interesting conversation because it triggered a perspectival shift for me and crystallized some ideas that had been floating about fuzzily in the back lots. Below, I’ll summarize the three main insights and how they’re interconnected.

Here are my slightly worked up notes of what seemed (to me) to be the highlight insights of the conversation. The ideas emerged from the three-way conversation but errors in recording and interpretation are mine. When I refer to “books” without qualifying the term, the meaning is “books published by conventional trade and university presses.” When I refer to “conventional publishing,” I mean “the existing mainstream system of developing, producing, and selling books.” Or something like that.

1:few vs. 1:many mappings. Throughout acquisition, editing, market positioning, and sales, conventionally published books seem to be categorized like files in a filing system. That’s to say that there’s implicitly a 1:few (or even 1:1) mapping between a book and where in the categorization system it is filed (e.g., Business—Economics or Restaurants—Technological innovations). This isn’t only about the formal subject classifications which publishers assign to books for the librarian’s use. It also seems to be how publishers and booksellers think about books as having audiences defined by being interested in a small number of relatively closely related topics. Is this a holdover from the library and bookstore physical addressing and shelving problem where any physical book should only be shelved in one place? Today, books are bought both online and offline and in digital and physical editions; in particular, online and in digital form, a book can be shelved in an arbitrarily large number of categories (1:many mapping between book and the categories it lives in). Nonetheless, the difficulty conventional publishing has with 1:many categorization seems to make it hard for books to be published if they cross disciplines or interests, if they represent emergent disciplines or interests, or if they appeal to fragmented and diverse audiences—and all three scenarios are becoming increasingly important.

Ends vs. side effects vs. means. Conventional publishing focuses on the end product, which is the finished book. Many (most?) authors get relatively small advances, so they end up taking on much of the risk of producing the finished product (costs of doing research, writing and revision, etc). Yet, selling large numbers of finished books (whether online or offline) requires big marketing budgets and the expense of distribution infrastructure—so there’s some justification for small royalty percentages for authors in conventional publishing. The result is that when authors make money from publishing books, they often do so more from the post-publishing side-effects than from royalties. These side-effects include merchandise sales, speaking engagements, consulting opportunities, or licensing. This explains the profusion of cookie-cutter books produced to generate such side-effect revenue streams. Recently, there’s been an emerging practice of authors monetizing the means to get to the end product. In other words, these authors find a way to make money from intermediate work product which may or may not result in a finished book. One example might be an author who wants to write a book about a new approach to project management and develops the book by selling a workshop on project management which test-runs the book’s content and organization. Another example might be an author who wants to write a book about independent consulting and posts a series of short articles mapping to the book’s parts which (maybe) act as lead-generation for intermediate consulting revenue (👋 Tom!). When authors monetize the means of producing finished books, they probably achieve better product-market fit and build stronger marketing platforms for the resulting books.

Aggregation vs. disaggregation. Conventional publishing houses—especially the big ones and university presses—aggregate some or all of these functions: Find authors; develop embryonic book ideas; have a reputation that helps readers reduce search cost for new books; produce (edit, copyedit, design, print) books; market, promote, and sell books; distribute books; manage rights (translation, audio, film, etc) deriving from books; produce otherwise economically unviable books through a portfolio approach. Do all these functions need to be combined? And how many houses are doing all of them very well now? The first two insights—1:few categorization and ends/side-effects monetization models—suggest that conventional publishing might find it especially hard to be good at the high-uncertainty functions: finding authors, developing embryonic book ideas, and producing otherwise unviable books. Over time, they might also therefore lose the ability to help readers find unexpected new books that are also good. And they already seem to be stuck with legacy production and distribution workflows and processes that cost more (in both time and money) and can be way less effective than newly available alternatives. The problem has at least two roots: legacy and mindset. Any new publishing house could escape some of the legacy problems. But a new publishing house might have to decide at the outset to focus on only a handful of the functions of conventional publishing (i.e., to disaggregate these functions) to be able to inject innovation—via increased tolerance for uncertainty—into the process of finding authors, developing ideas, and producing apparently unviable books. And if a new publishing house did do this, it might not look like a conventional publishing house at all. Instead, it might look like a reading group or a salon.

Conventional publishing probably isn’t going away soon, because conventional readers will always want conventional books—and there’s a lot of conventional readers. Yet there’s a burgeoning population of people creating weird, illegible ideas on the one hand, and large but fragmented audiences that may want to consume these ideas on the other. And conventional publishing doesn’t seem so great at connecting the two.

🤔

You’ll hear from me again next Wednesday. I’m currently noodling on what I hope will be a concise issue on the zoom factor in uncertainty—which is especially relevant to us now.

This old world won’t change because you’re trying.

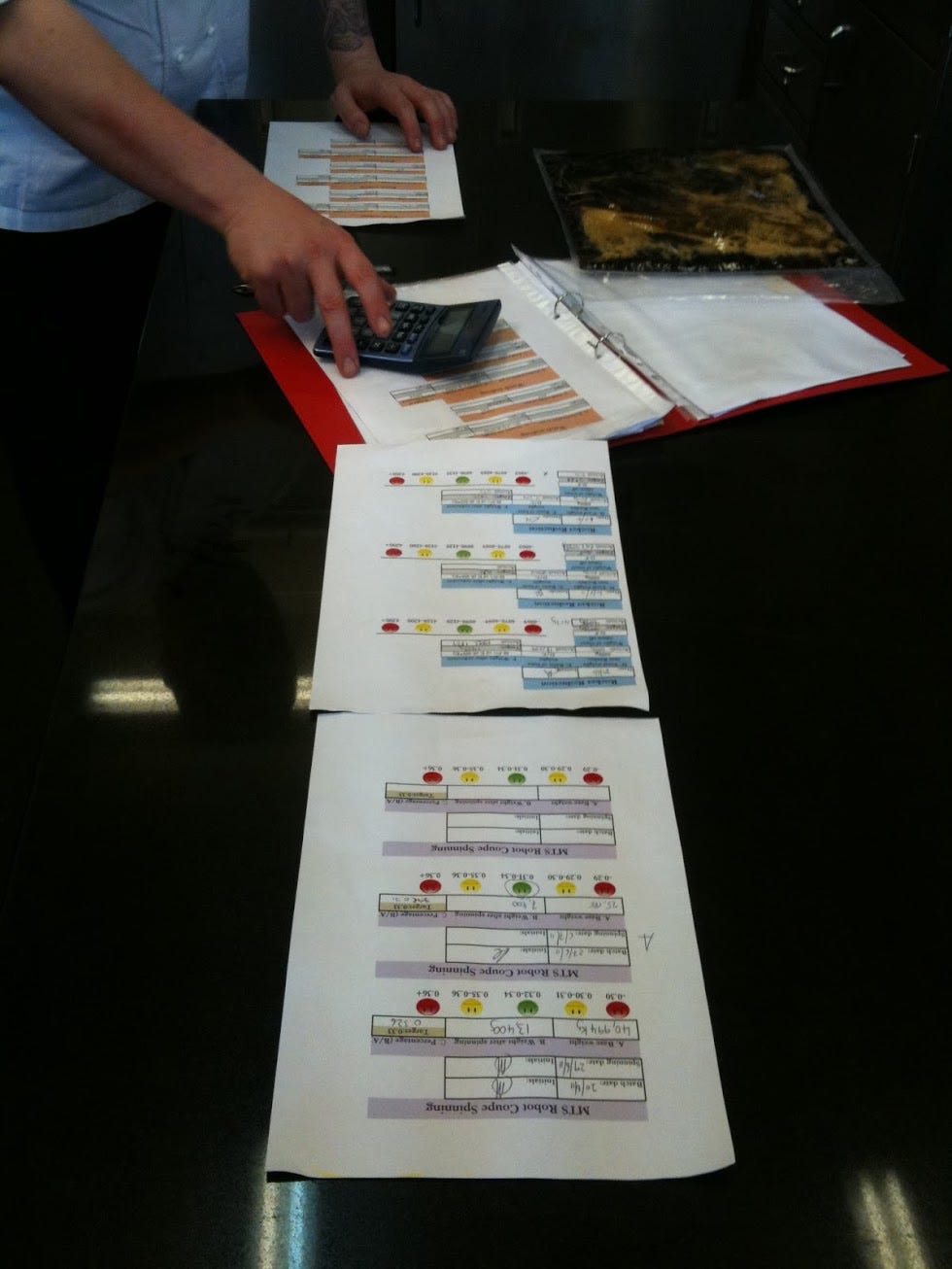

Photos: Until Issue #52, each week’s photos will be selected from the thousands I took during fieldwork for the book. This issue’s photos are pastry photo-editing for Modernist Cuisine at Home (The Cooking Lab, 2012), preparing an emulsion the right way (ThinkFoodGroup, 2010), your run-of-the-mill cooking supply cabinet (Patagonia Food Lab, 2011), and debugging the Mad Hatter’s soluble watch (The Fat Duck, 2011).

“Bonus”: I self-audited my media consumption habits for WITI? You can experience the horror here.

Find me on the web at www.vaughntan.org, on Twitter @vaughn_tan, on Instagram @vaughn.tan, or by email at <uncertaintymindset@vaughntan.org>.