#9: Tradeoffs

New year, new you.

This is yet another of Vaughn Tan’s weekly attempts to make sense of not-knowing. The ideas below may be only partially baked.

🎉 Felicitations for the new year and the new decade. 🎉

Everything seems to be business as usual. An intricate system of global and local logistics delivers me books and essentially anything I could want within hours, the shops down the street overflow with tropical fruit and assorted confections, the internet offers endless opportunities for procrastination. Except: under the veneer of normality and the socioculturally enforced holiday jollity lurks a sense of unease.

Brazil, Indonesia, and Australia are still/were on fire; there is at least one massive, still-growing, clump of garbage in the ocean; the previously stable US/EU-led world order is transitioning to one dominated by a China/Russia axis; 3D-printed projectile weapons are now easy to produce; most municipal water and commercially available food is filled with stuff I don’t want to eat and drink; the air in many major cities is terrifyingly contaminated; inequality seems to be growing everywhere (though the measures claim otherwise); inflation is galloping away (though the measures claim otherwise); demagogues increasingly control the politics of major democracies; governments everywhere are literally printing money to keep economies growing or, let’s be honest, afloat; food substitutes are big business; etc.

On the surface, all is prosperity and progress. Buy some narcotic substance delivered in a nicely designed rechargeable object and feel a surge of well-being and denial. Make purchases on a precision-engineered glass and metal telecommunications device, then use it to watch a video of a cat in a shark costume chasing a duck while riding a Roomba. Snack on some quality-assured meat-replacement grown in a vat, while reserving a Cybertruck today to be one of the first to ride about in style while insulated from your highly uncertain environment.

In this situation which we all face, there are two possible options.

Proceed with business as usual by navigating fleetly to your chosen online video and shopping portals and through their good offices sweep the lingering unease under the rug (sold separately);

Grit your teeth and force yourself to see the world as it really is.

Business as usual combines the optimism that things will be alright and pessimism that nothing can be done to root out the source of the unease. It works well until it stops working—and nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. Rebecca Solnit writes:

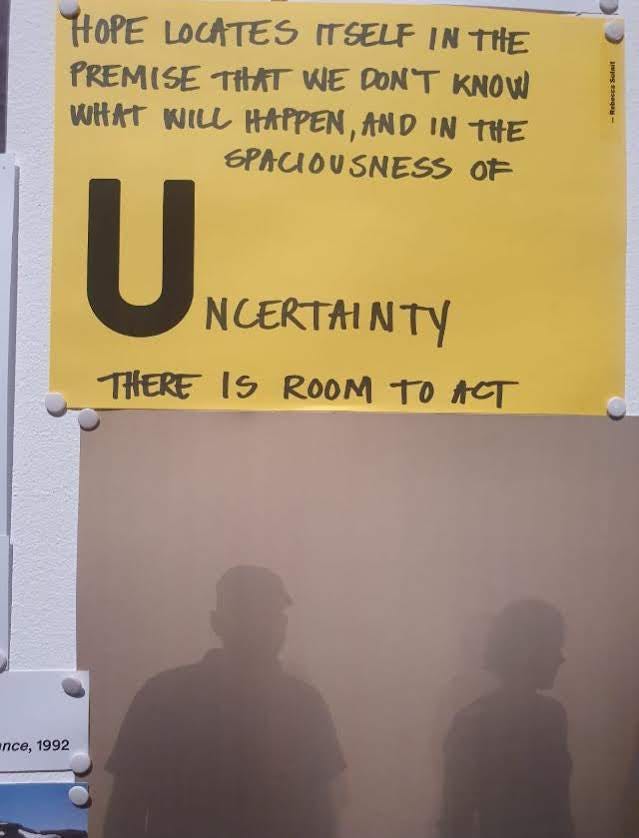

Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognise uncertainty, you recognise that you may be able to influence the outcomes—you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists adopt the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting.

(Seen at the Olafur Eliasson show currently at Tate—photo by Jimmy Tassan Toffola)

If being brutally honest, only option 2 is viable. Really looking at the world means being painfully frank about the tradeoffs you are and (this is especially important) are not willing to accept.

If you must have the profusion of children, the stable corporate job, the large house with garage, your options for being responsive and flexible are (all else equal) more limited than if those are things you are willing to give up. If you must have the flexibility to move cities at a moment’s notice and the ability to spend the bulk of your work life learning new things, options for acquiring children, corporate jobs, and mortgages are (all else equal) more limited than if those are unimportant. Good health, time, and money—which are all finite resources—can sometimes make it possible to get closer to squaring the circle of choice and tradeoffs but the underlying problem always remains: we must choose because we have limited resources, and every choice implies accepting a configuration of tradeoffs.

Setting goals and making decisions to achieve them becomes easier the more explicit the tradeoffs are. (Instead of being left comfortingly implicit and hazy—on which, see any corporate goal-setting exercise which invariably sets goals without forcing a discussion of what tradeoffs those goals will entail). Strategy, which is nothing more than deciding how to take action to achieve goals, only really works when you voluntarily choose the tradeoffs you are willing to make instead of being forced into accepting tradeoffs that you have accidentally chosen by being unclear about them.

This is true about trivial decisions like strategizing about what and how to eat, which these days has become a cause of major angst for nearly everybody. Food can be tasty, healthy, convenient, or inexpensive; but it’s rarely all four at once. Being explicit about which tradeoffs are acceptable—say, that it’s okay for food to sometimes but not regularly be unhealthy, as long as it is also delicious—makes it possible to have the occasional Zinger® Tower without the usual feelings of intense self-hatred. It also clarifies how the rest of your eating should work: mostly eat food that is minimally processed from recognizable raw materials by actual people you know, including yourself. For example.

Being explicit about tradeoffs also clarifies major life decisions such as choosing whether to relocate permanently to LA, or whether to abandon a career developed over many years. Choosing between staying in (say) London or moving to (say) LA actually means choosing between the set of tradeoffs implicit in living in London (extraordinary pollution, grey skies, being able to cycle everywhere or use public transit, proximity to Europe, etc) and the set of tradeoffs implicit in moving to LA (easy availability of tacos, abysmal traffic, sunshine, media industry people).

For those who like tacos and sun and don’t mind traffic and media people—and dislike pollution, greyness, proximity to Europe, and public transit—the choice is clear. But lovers of sun, tacos, being near Europe, and public transit, who hate traffic, overcast skies, air pollution, and media people, can only make a good decision about LA vs. London after rigorously explicating the tradeoffs they are and aren’t willing to accept. When you force yourself to decide that tacos are your absolute top priority, for which you are willing to accept bad traffic and distance from the low-intervention wine paradise that is Europe, then your choice becomes clear again. (If only all strategic decisions were as easy.)

The correct fundamental question to ask in strategy is not, “What do you want?” but, instead, “What do you think you are willing (and unwilling) to give up to get what you think you want?” As usual, there’s not a simple, clear, and accurate way of capturing what needs to be done, because it goes beyond conventional, coolly rational cost/benefit or pro/con analyses.

That latter question about tradeoffs can never be definitively answered in advance. Many—possibly all—beliefs about tradeoffs are necessarily hypothetical until tested. Move to LA for a few months and maybe discover that the tacos really are great, that media people aren’t so bad, and that cycling everywhere is possible. And that being an 11-hour flight instead of a two-hour train from France is a surprisingly important consideration. (For example.) The uncertainty of the future and of our evolving idea of our desires both frustrates decisive action and offers opportunities for previously unconsidered satisfaction.

That the question cannot be definitively answered in advance doesn’t mean it should be ignored—the point is not the answer but the act of asking of the question. A practice of rigorously articulating and prioritizing tradeoffs is part of a way of being in the world that is personally honest because it forces a coming-to-terms with personal subjectivity and fallibility. And this self-knowledge—knowing what internal un/certainties you have—is the basis for being able to use the space for action that external uncertainty offers.

New year, new you.

… if you haven’t already, and/or find me on the internet at www.vaughntan.org, on Twitter @vaughn_tan, Instagram @vaughn.tan, or by email at uncertaintymindset@vaughntan.org.