Don't wait until it's obvious.

Hello friends,

tl;dr: Most strategic mistakes don’t come from just bad planning. They come from misdiagnosing the types of unknowns your strategy is set up to deal with. And the consequences of misdiagnosis are rarely obvious — until it's too late.For the last 15 years, I’ve been focused on untangling the confusion between two fundamentally different types of unknowns: risk and uncertainty.

(The quick summary: Risk is when you know all the possible actions you could take, all the outcomes that might result, and the precise and accurate probability connecting actions with outcomes. Uncertainty is when you don’t know all possible actions, outcomes, and probabilities connecting actions with outcomes.)

With risk, you know almost everything about what you don’t know; with uncertainty, you know much, much less. Risk and uncertainty are not the same thing, and you set yourself up for failure if you mistake one for the other.

A question of outcomes

Last April, Jerry Neumann sent me down a rabbithole when he emailed me with a question: How would you know, after the fact, if someone had been making decisions based on uncertainty vs. risk? Would the distribution of outcomes look different?

I spent the better part of the last year with that rattling around the back of my mind because the more general form of that question is one which we face every day: How do you know if you’ve misdiagnosed a situation as risky when it was actually uncertain?

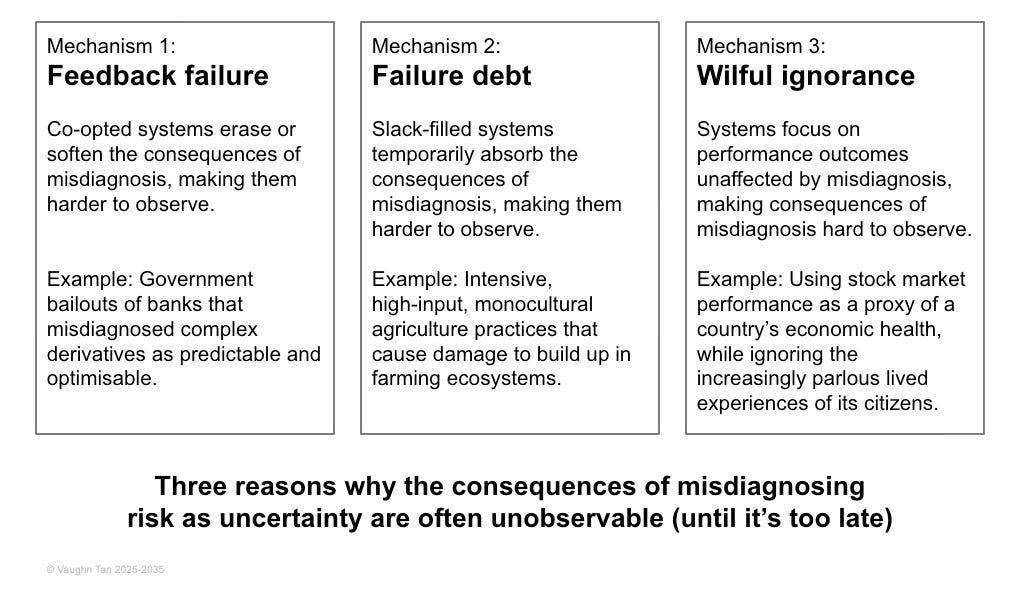

Three reasons it’s only obvious when it’s too late

The answer is: Usually, you don’t know — until it’s too late. This is especially true for powerful actors operating in slack-filled systems, but what happens to them affects everyone else. There are three reasons for this:

Mechanism 1: Feedback failure

When actors become powerful enough that the system becomes co-opted to protect their interests — when the system is captured by the actors — the consequences of misdiagnosis can be erased or significantly reduced.

Example: Running up to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, many U.S. banks assumed that complex derivatives were understandable, manageable risks. They turned out to be unpredictable. Many banks should have failed from their losses—but only a handful did, because the government deemed the banking system too systemically important and bailed many banks out.

When systems are captured, feedback loops are broken and misdiagnosis will not reveal itself in performance.

Mechanism 2: Failure debt

A system with a lot of slack and excess capacity can absorb a lot of bad consequences from misdiagnosis before being observably affected.

Example: High-input monocultural agricultural practices continue to give high yields because the ecosystem is able, temporarily, to absorb gradually accumulating damage (depletion of soil organic carbon, buildup of agrochemicals, etc).

When systems have enough slack to absorb bad consequences, performance will not clearly indicate misdiagnosis.

Mechanism 3: Willful ignorance

Misdiagnosis is hard to see when outcomes unaffected by misdiagnosis are measured (and outcomes affected by misdiagnosis are not).

Example: Focusing on stock market performance as a proxy of a country’s economic health in deciding economic policy, while ignoring the increasingly parlous lived experiences of its citizens (the so-called Wall Street/Main Street divide).

When performance is measured using non-informative outcomes, performance will not clearly indicate misdiagnosis.

When the rubber band snaps

With all three mechanisms, the real consequences of misdiagnosis only become obvious when it’s too late to fix them:

Banks fail faster than the economy can bail them out.

An ecosystem collapses overnight instead of eroding gradually.

An electorate turns on the system that left them behind.

When the rubber band finally snaps, what looked like a predictable, optimisable situation of calculable risk is suddenly shown to be fragile, uncertain, and unoptimisable.

This is one way to interpret the rapid unraveling of post-WWII norms around national sovereignty and the use of force.

For decades, investment and security decisions—especially in Europe—were built on the assumption that nations would respect national borders and uphold treaties. The Western international order functioned on an expectation of good-faith engagement, for ultimately utilitarian ends.

That expectation collapsed in the last month.

Now, European governments are scrambling to rewrite their national security and defense policies, finally recognizing that a world they thought was risk-based was actually uncertain all along.

After the fact, analysts will say the warning signs were always there, that this was inevitable. If so, then a different mindset was always warranted—one that acknowledges how rare and fleeting stability and predictability really is. I call this an uncertainty mindset, and it is what my first book is about.

This new geopolitical crisis has forced international coordination that would have been unthinkable even months ago. But this is a reactive scramble—a last-minute attempt to build resilience after the fact. The real strategic questions are:

What if governments had acknowledged this uncertainty earlier?

What choices would they have made differently if they hadn’t misdiagnosed the situation as risk?

Don’t wait until it’s obvious

This insight applies beyond geopolitics to business and policy. Misdiagnosing the unknowns you face can lead to decisions that seem reasonable — but they leave you unprepared for the moment when the misdiagnosis becomes undeniable. By then, you’re reacting instead of leading.

So, the real strategic questions are:

What are you currently treating as a risk that is actually uncertain?

What choices would you make differently if you’re not misdiagnosing the situation as risk?

The obvious guidance here is not to wait until it’s too late, and to invest early in an uncertainty mindset that helps you think clearly about what types of unknowns you face.

If you’d like to have a chat about building an uncertainty mindset in your organisation, just reply to this email (or get in touch with me some other way).

See you here in a couple weeks,

VT

I’ve been working on tools for learning how to turn discomfort into something productive. idk is the first of these tools.

And I’ve spent the last 15 years investigating how organisations can design themselves to be good at working in uncertainty by clearly distinguishing it from risk.

Have you looked at Frank Knight's work? Nick Bloom on Knightian uncertainty: 'One can consider two types of uncertainty: risk and ambiguity. This distinction was made by Professor Frank Knight of the University of Chicago in his 1921 book "Risk, Uncertainty and Profit". He identified risk as occurring when the range of potential outcomes, and the likelihood of each, is well known – for example, a flipped coin has an equal chance of coming up heads or tails. One could answer a question like “How many times would you expect a coin to come up heads if it is tossed 100 times?” with both a best guess (50) and a “confidence interval” (for example, in this case there is about a 95 percent chance that a fair coin will come up heads between 40 and 60 times). In contrast, what has become known as “Knightian uncertainty” or “ambiguity” arises when the distribution of outcomes is unknown, such as when the question is very broad or when it refers to a rare or novel event. At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, there was a tremendous spike in Knightian uncertainty. Because this was a novel coronavirus, and pandemics are not frequent events, it was very difficult to assess likely impacts or predict the number of deaths with a high degree of confidence.'

the examples appear to reflect a single archetype: sudden unexpected phase change in a system. are there others you can point at?

also related - when you say "types of unknowns" are you being binary - risk or uncertainty - or do you have a finer-grained taxonomy? i assume that if you diagnose your context correctly, you should be able to figure out what _particular_ type of unknown might exist and this can be better prepared for. Just avoiding the situations you discuss does not seem doable to me. for example, as a bank, you are probably happy to be "too big to fail" and would not want to avoid the advantages it gives, even if it screws up your early-warning system.