Boring and uncomfortable (wk 52/2025)

Why Boring Tiny Tools are good; what to do when there's nothing to do; being uncomfortable; billionaire babies, moneymaking, choosing deviance.

Hello friends,

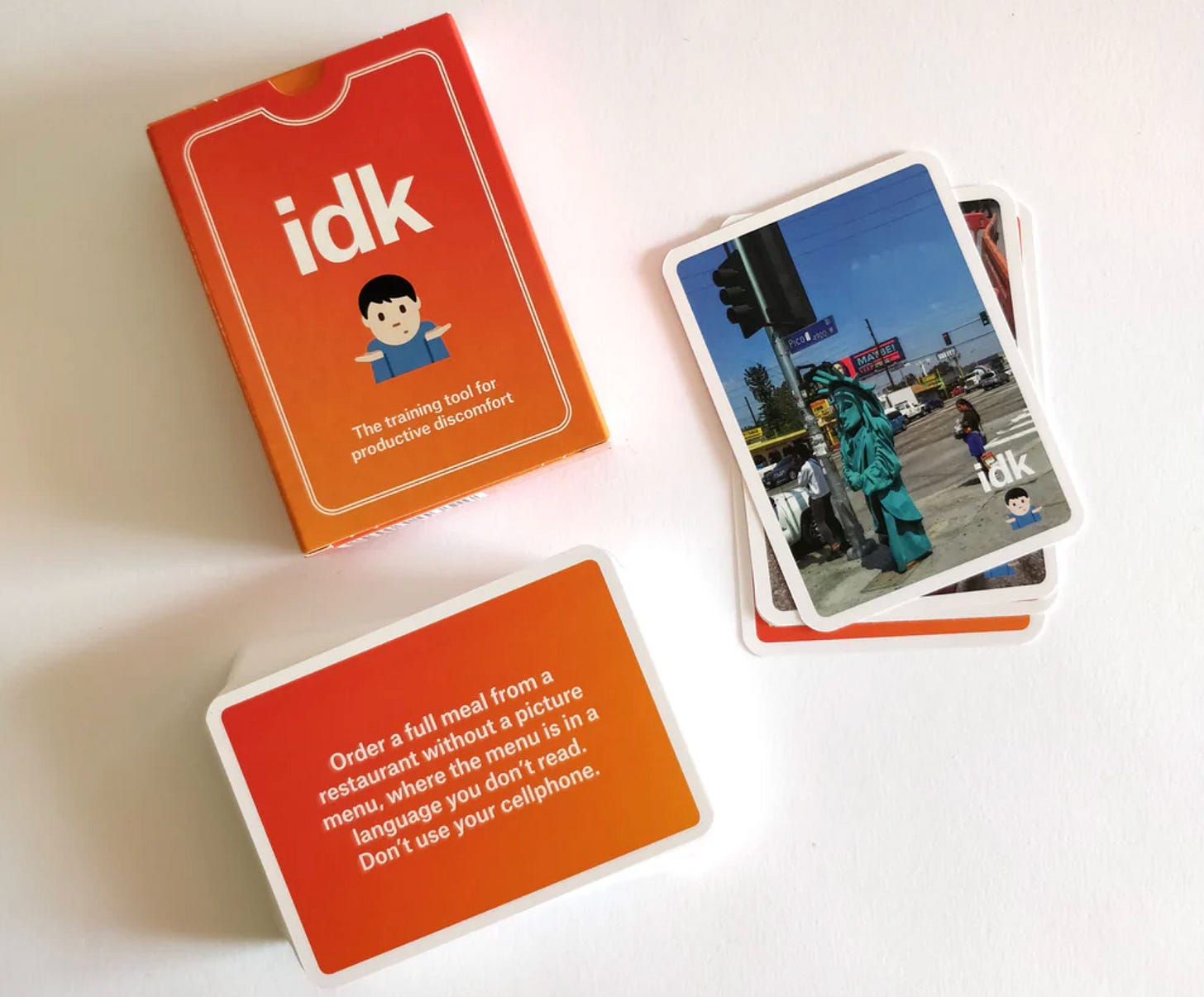

Crass commercialism: idk, the world’s first and only tool for learning how to be productively uncomfortable, is once more available in Europe and the US! Read more below about why cultivating productive discomfort is essential.

In early June this year, I was trying to write my first software specification for a vibecoding session. I needed to build a tool I needed for a consulting engagement. I’d written product requirements before at Google, decades ago. But this felt uncomfortably different. The task was ostensibly simple: describe what I wanted a tool to do so that an AI could write the code to do it. In practice, the entire frame had shifted. What worked for vibe coding with AI bore almost no resemblance to the PRD discipline I’d learned in a corporate environment.

It would have been easier to hire someone. Modern life encourages us to pay someone else to handle our discomfort. A nontrivial part of the modern economy is built on the premise that people will pay to avoid discomfort. Food delivery so you don’t have to cook. Task outsourcing so you don’t have to learn new skills. Template solutions so you don’t have to think through problems from first principles. This systematic elimination of discomfort from daily life has made us remarkably efficient at avoiding things we’re bad at. But it’s also made us progressively worse at dealing with discomfort at all.

The problem is: Uncomfortable situations are usually the ones with the most potential for learning and innovation. If we continually avoid discomfort—and modern society increasingly pushes us to do exactly that—we lose our ability to do uncomfortable things. The muscle that lets us push through initial confusion, sit with not-knowing, and slowly build competence in unfamiliar territory weakens from disuse.

So I didn’t hire someone to write my software. Instead, I structured the discomfort deliberately. I started with scoping tiny projects with low stakes so I could abandon anything that didn’t work. I built a tool to process receipts for my business accounting. Another to organise research and output production. Another to make my tangle of travel bookings reliably interrogatable. Each tool taught me something about writing specifications that an AI tool could actually work with. And each small success built my capacity for slightly more uncomfortable next steps.

Over the last six months, I’ve built a bunch of stuff. Some of it helps me run my tiny consulting business more reliably. Others I have bigger intentions for. (Such as the prototype of a tool for helping students learn how to think critically while using AI tools). Building all this required pushing through the initial discomfort of not knowing how to do something, and structuring that discomfort in ways that made learning possible.

I eventually realised that I’d implemented a version of my own training programme for productive discomfort. Not all discomfort is equal. Some discomfort is just suffering—pointless, grinding, soul-destroying work that teaches you nothing except that you hate it. But productive discomfort is different. It’s the discomfort that comes from being at the edge of competence, doing something slightly harder than you’re comfortable with, in a context that’s designed to support learning rather than punish failure.

Modern life seems to eliminate both kinds of discomfort indiscriminately. We lose access to the productive kind along with the pointless kind. This is bad, because productive discomfort is how we grow. It’s how we develop new capabilities. It’s how we stop being helpless in the face of unfamiliar situations.

Back in 2021, I developed idk. It’s a series of prompts that help users practice being more comfortable with productive discomfort. Each card presents a small challenge that creates discomfort that is intentionally designed to expand horizons, change perspectives. The people who have bought it seem to like it.

Earlier this year, a catastrophic logistics failure. My third-party logistics provider lost all my stock in a warehouse transfer. (They also got bought by another company and became five times more expensive.) This became a masterclass in productive discomfort because I was in the middle of several other projects. The easy thing would have been to just shut down idk sales and move on. But I decided to push through the discomfort of abandoning a logistics partner I’d worked with for years to track down recoverable inventory, rethink how I distribute and fulfill orders, and rebuild my supply chain from scratch. As of this week, idk is finally back in stock in the US and Europe. Not in time for Christmas delivery, but idk would make a good gift for the new year…

The logic here is the same whether you’re learning to write software specifications, practicing discomfort through card prompts, or navigating a small business catastrophe. We need deliberate practice at being uncomfortable. We need to design systems and situations that put us into situations of productive discomfort which are carefully structured, safe enough to learn from, and which build progressively on our slowly growing capacity to handle uncertainty.

Otherwise we just keep paying for convenience until we can’t do anything uncomfortable at all.

Writing

Boring Tiny Tools — On why digital transformation fails when organisations try to do it with Big Fancy Software instead of Boring Tiny Tools: narrow-scoped tools that fit seamlessly into existing workflows. I argue for a fundamentally different approach to product development that focuses on designing software that only replaces work that requires no human judgment, serves tiny userbases, offers users exactly what they need, and uses only off-the-shelf components. (22/12/2025)

Doing nothing: a reading list — A short and non-exhaustive list of ten things to read before spending time with nothing much to do. In different ways, these things all show how removing one kind of variation gives other kinds of variation space to emerge and become visible. (15/12/2025)

Elsewhere

“For the first time in history, weirdness is a choice.” (I’m not so sure about that, tbh.)

See you next year,

VT