Hello friends,

Last Thursday morning, an unmarked white van pulled up next to the table outside the tabac where I was having a crappy coffee meeting. It was a Fedex delivery vehicle. The driver handed me a package through the open window, and drove off in a cloud of diesel particulates — “pas besoin de signer!” No need for ID verification either, apparently.

The week before, I’d had the following SMS exchange (loosely translated):

Fedex: yo mate. have your Fedex package. u home in 10 min?

VT: sorry, i’m away. back next week. do i have to reschedule on the website?

F: cool cool no just txt me at this number when u get back

... A week later ...

VT: i’m back tomorrow, will be home by 9.30am.

F: see u 9.30 tm

... The next day at 9am ...

VT: later is ok? i’m nearby but won’t get home until 10/10.15.

F: where u at

VT: [I tell him where] i’m in the red t-shirt.

VT: are you sure this is ok

F: 10 minThat Fedex delivery was entirely unlike any I’ve had before in other big cities: extraordinarily effective and a great user experience. But would it work in a real Big City? Could something like this #scale?

I was still bemused by it this Monday, when I had a regularly scheduled (!) Zoom catch-up with a faraway friend whom I’ve still not met in person (!). I have these catch-ups with a small handful of different people, and they all work the same way. There’s no agenda. We’re just talking about stuff we’re working on and thinking about. The conversations go in unexpected directions and bring ideas together in unexpected ways. It’s great. This is one good outcome (for me) of what’s been a kinda crummy few years for the world and most people in it.

Monday’s catch-up was with Alex Komoroske, in California. He mentioned that he’d been thinking about how LLMs will eventually move us back to a world where more people use highly context-specific, unpolished, duct-tapey software. LLMs are already helping developers write code more quickly. (Here’s an explainer about using LLMs for code generation). With time, LLMs and tools like them will probably get many people (especially non-developers) comfortable with home-brewing code to do what they very specifically need, albeit in an unscalable, inelegant, highly unoptimised way.

(As an aside, my view is that the only currently reasonable framing of “AI” is as a very powerful tool we are still learning how to use. Writing good code is a design process, and thus inherently a meaning-making process. Tools — code libraries, version control systems, code editors, etc — help humans do this meaning-making, but tools cannot do the meaning-making for us yet. The mistake is to think that they can, and the big challenge we face with “AI” today is understanding what meaning-making means in the context of “AI” tools.)

Another way to say it is that LLMs will let regular folks build kludgy but highly customised software solutions to their specific (and potentially idiosyncratic) needs instead of relying on a highly efficient large-scale software product built professionally by someone else. At the moment, reducing the barriers to this kind of application self-sufficiency seems like a good thing.

Situated software

Alex described this kludgy but highly tailored stuff as situated software. The concept was new to me, so I looked up and read the 2004 (!) essay by Clay Shirky which popularised the term. This is how Shirky defines it: Situated software consists of “form-fit tools for very particular needs, tools that fail most previous test of design quality or success, but which nevertheless function well, because they are so well situated in the community that uses them“ — in contrast with Web School software built for large-scale audiences of generic users.

Shirky writes: “We've been killing conversations about software with ‘That won't scale’ for so long we've forgotten that scaling problems aren't inherently fatal. The N-squared problem is only a problem if N is large, and in social situations, N is usually not large. A reading group works better with 5 members than 15; a seminar works better with 15 than 25, much less 50, and so on.”

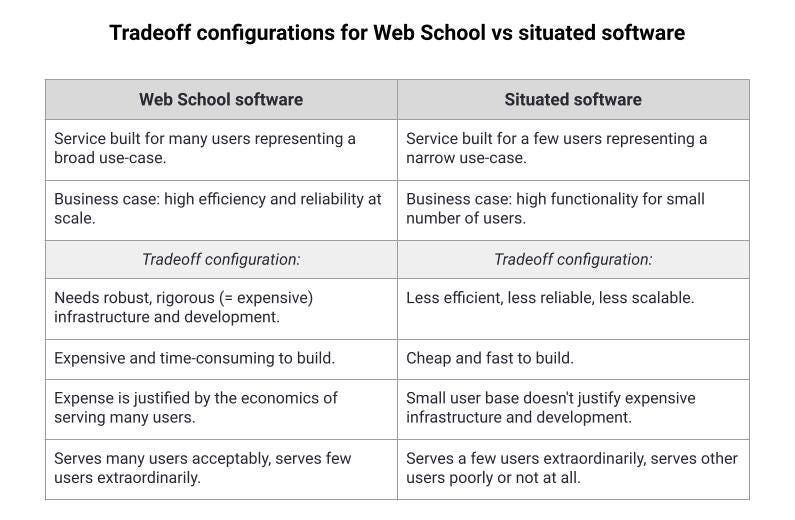

Sometimes, situated software works better for the specific small group of users it is built for even if it isn’t mega-scalable, super-reliable, and hyper-elegant. In other words, situated software isn’t just “a degenerate case of ‘real’ application development” (Shirky again) — it has a particular configuration of acceptable (and unacceptable) tradeoffs that makes sense sometimes. But you have to make the tradeoff configurations of the two approaches explicit before you can choose correctly between them, before you can figure out when that sometimes is.

If you’ve been reading what I write for a while, you’ll know that I think conventional goal-setting approaches are defective because they focus only on articulating goals instead of un/acceptable tradeoff configurations. All organisational goal-setting needs to focus not just on goals themselves but what tradeoffs should and shouldn’t be made to achieve those goals. And giving the tradeoffs themselves more consideration makes better strategy too.

Here’s an example. The logic of situated software is that it serves a few extraordinarily, even if it is too brittle — too unreliable, too underresourced, too easily broken — to serve many others well (or at all). Brittleness here is framed as an implicitly bad thing, a tradeoff we have to accept to get high functionality for a small group of users that cannot afford to pay for high reliability and efficiency.

I think this is wrong.

Good brittleness

Brittleness doesn’t always have to be bad. Let’s take a step back and think about not just software but things more generally: systems, products, buildings, etc. Good brittleness is when a thing is highly tailored to a specific environment/need and breaks quickly when the environment/need changes. If that thing is also designed to be easy to repair/upgrade so it works again, this form of good brittleness becomes even better.

Bad brittleness provides little benefit to the system. Good brittleness quickly discloses system-impacting change and enables cheap and fast adaptation to that change.

The soft carbon steel knife is an example of good brittleness in a physical product. Simplifying a lot: a kitchen knife can be made of soft, easily tarnished carbon steel or hard, stainless steel. A stainless steel knife can retain its sharp edge through quite a bit of abuse, so you don’t have to be as careful when using it. But when you do manage to fuck up the edge — say by chopping up some massive gritty leeks — repairing the nicked blade requires time-consuming, skill-intensive regrinding of the whole edge. This is a form of failure debt.

A carbon steel blade is soft by comparison. It loses its edge quickly. You must pay attention to what you cut with it and what surface you cut on (can’t use those idiotic glass cutting boards). The edge needs to be realigned into sharpness with a hone every day. But this maintenance is easy and quick to do.

Good brittleness changes the behavior of those using the thing. The stainless knife promotes more aggressive, less careful cutting and infrequent but intensive attention to maintenance of blade. In contrast, the good brittleness of the carbon steel knife promotes more careful and precise cutting and frequent but easy maintenance.

The almost terrifyingly flexible and accommodating Fedex delivery model in Marseille’s 2nd arrondissement is probably a systems/processes example of good brittleness.

Good brittleness is intuitively aligned with Christopher Alexander’s approach to building adaptive, adaptable, and humane buildings, and is part of my continuing affection for the idea of maintenance by design, the practice of designing whole systems for environmental perception and response.

So maybe an upgraded way to think of good forms of situatedness would be as things that are both A) informed by specific situations and also B) easily responsive to how those situations change. In other words, situatedness in which the brittleness that comes with (A) is also designed to make (B) happen. Basically, situatedness becomes better with good brittleness.

In a world that’s changing more often and unpredictably every day, learning how to build things that have situatedness and good brittleness seems way more important than focusing only on building large-scale systems that accumulate failure debt.

Stuff I’ve seen recently

What strategic possibilities arise when we have not-knowing about actions and outcomes?

Weatherspark, a good tool for understanding comparative weather.

Why algorithmic perfection is hard when you’re embedded in a situation.

Not-knowing: Connecting actions and results

The seventh episode in my Interintellect series about not-knowing is about causation. Making good strategy is hard when you don’t know how particular actions are connected to particular outcomes. At the same time, not-knowing about causation can also offer freedom to act under specific conditions. This can be a strategic and tactical advantage. We’ll talk about four types of not-knowing in causation and how each type offers different constraints and opportunities for strategy and tactics.

Date and time-change! Tuesday, 25 July, 5-7pm CEST. More information and tickets. And here are some backgrounders on thinking more clearly about not-knowing from previous episodes.

See you in a couple of weeks,

VT

Oh shucks, this post being about software, I have so many thoughts. I will have to come back to this later this weekend.