The "good" experiment

Experimenting as a way to deal with uncertainty ... and how to design "good," viably sneaky experiments.

Hello friends,

Welcome back from summer (though Europe is in yet another heatwave). This issue is about experiments as a way to deal with uncertainty, and how to design good experiments. And a plug at the end for Episode 9, on futurity, of my monthly discussion series on not-knowing. Also, if you like this (or any other issue) do not hesitate to click on the “Like” and “Share” buttons — really, don’t hesitate for even a moment.

tl;dr: Good experiments are an appropriate way to act when faced with both uncertainty and an uncertainty-averse organization. At a minimum, a good experiment must have a hypothesis about a mechanism that the experiment will investigate, an actionable insight if the hypothesis is supported, and an actionable insight even if the hypothesis is not supported. A good experiment can be made easier for an uncertainty-averse organization to swallow by redesigning it to be as small, cheap, and fast to execute as possible, while providing all three of the abovementioned characteristics.

It’s happened yet again to Organization Person — your usual well-meaning leader/manager trying to do a good job in their organization. Everything had been going so well but now, once again, OP faces a situation where The Correct Path Forward is obscured by fog.

OP could be a product manager in a MegaCorp tasked with building some new technical infrastructure where suppliers of key hardware are still figuring out the underlying technology. OP could equally easily be a startup founder trying to find product-market fit where neither the product nor the market have fully emerged, or a public servant tasked with developing new policy tools to address a still-emerging problem, or a foundation program manager responsible for making grants for a not-yet-stable set of desired outcomes.

OP just doesn’t have enough information to use the usual cost-benefit analyses or expected value calculations to build strategy and tactics — unless OP wants to make up some meaningless numbers, of course! In other words, OP faces true unquantifiable uncertainty, not just calculable risk. (Here’s a short piece about the difference between risk and uncertainty, and another about how to think clearly about what is and isn’t risky.)

What is OP to do? I have a suggestion.

Empiricism and category error

A few weeks ago, I had breakfast with Cedric while I was back in Singapore. Cedric’s thing is business expertise, so we were discussing what successful companies have done to be successful. He prefers business expertise that is based in experience. I also like this empirical approach much more than approaches that come out of pure theory — but one of the challenges of empiricism is that it tends to lack theory.

This means that empiricism often can’t identify when it applies learnings from one type of setting to a different type of setting where the mechanisms work differently: empiricism often makes category errors. The particular category error I currently object to most is interpreting and acting on all situations of not-knowing as if they are risk.

Category error shows up in empiricism a lot. Uncertainty often paralyses people and organizations; they do nothing because they don’t know what to do. Cedric and I also talked about the empiricist fondness for “action bias” even in situations of uncertainty — the idea that doing something is better than doing nothing.

This becomes a problem when action bias gets extended to mean “doing anything is better than doing nothing.” My own view is that doing something appropriate is better than doing nothing — but doing something poorly considered for the sake of action bias is kinda dopey.

This is how we got on the topic of experiments in uncertain (vs only risky) situations.

Experimentalism

Experimentation is empiricism that is appropriate for uncertain situations. When properly done, experimentation promotes learning about the situation and forces clearer thinking (or at least reveals when thinking is not yet clear).

In the last year, I’ve started running workshops for participants from organizations facing uncertainty. The point of these workshops was to get each participant to design just one experiment that was useful in figuring out something about their business — the three characteristics outlined below — and then to refactor the experiment to be so small and so cheap that it could be run immediately.

One of these workshops was for dealmakers at a big investment bank, another was for members of an agricultural commodity association, another was for leadership teams of a hybrid VC/PE fund’s portfolio companies. My point here is that experimenting properly as an appropriate response to uncertainty is generally applicable across lots of different contexts.

Our OP, facing the Unclear Path Forward, could benefit from some good experimentation.

What is a “good” experiment?

An experiment is “good” if it addresses a two-part problem.

The first part of the problem is that when the correct way forward is unclear, a high-stakes, big-time, expensive, singular strategy is inappropriate — good experiments that investigate different actions are much more situationally appropriate.

The second part of the problem is that all organizations hate anything that isn’t guaranteed to succeed (it doesn’t matter what the organization says about being pro-innovation etc) — good experiments must be designed to survive in organizations that instinctively resist experimentalism by being sneaky.

In other words, here “good” means that an experiment is expressly designed for learning in an uncertain situation and for sneaking past an uncertainty-averse organization.

The basics of a good experiment

To be good, an experiment must:

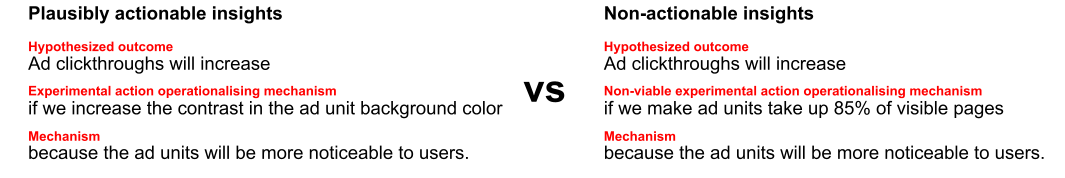

Have an explicitly stated hypothesis about at least one mechanism that the experiment will investigate, at a level of detail appropriate for your current level of knowledge of the situation. An example: “Ad clickthroughs will increase

if we increase the contrast in the ad unit background color because the ad units will be more noticeable to users.” Requiring an explicitly stated hypothesis and mechanism is not just a theorist’s fetish — the hypothesis and the mechanism are the only way to clearly express the intention behind the experiment. An informative experiment is impossible without being clear about the mechanism being tested, the way that mechanism will be operationalised in practice, and what the hoped-for result will be. Without a clear mechanism to test, the experiment provides no actionable insight even if it works.

Provide an actionable insight if the experiment shows that the hypothesis is supported. If ad clickthroughs increase, there is a clear and immediate action to take from this experiment: make ad unit backgrounds higher-contrast. This clarity and direct reduction to practice is only possible if the experiment is designed around experimental actions that are plausible in practice. Most mechanisms can be operationalized through many different actions — these actions are what experiments investigate. Experiments that test actions which could never be implementable are not actually useful — they may produce insights if they succeed, but those insights are not actionable.

Provide an actionable insight even if the hypothesis is not supported. If ad clickthroughs don’t increase, there are at least two possible reasons: either the underlying mechanism (noticeability) doesn’t increase ad clicks or the operationalisation of the mechanism (color contrast) isn’t effective. The actionable insight from the failed experiment would be to run experiments that operationalise noticeability in different ways (contrast, font size, color, placement, etc). Explicitly distinguishing between mechanisms and their operationalizations makes it more likely that even “failed” experiments lead to actionable insights. This likelihood increases when you choose to experiment with operationalizations where the insights from experimental success and failure are apparent even before you conduct the experiment.

Making it sneaky

A “good” experiment must also sneak past an uncertainty-averse organization until there is enough evidence of its desirability for it to survive unsneakily. This means refactoring experiments to be smaller, cheaper to run, and/or faster to deploy.

When refactoring an experiment like this, there will inevitably be tradeoffs. The experiment will not be as robust as if it had a larger sample size, or if the production values were higher, or if there was more time to collect more experiment responses. This is okay.

If the smaller, faster, cheaper versions of the experiment are informative enough, there will be time later for more robustly designed, bigger, more expensive, slower versions of the experiment. The purpose of refactoring is to get an uncertainty-averse organization to swallow the psychic horror of running an experiment (which might fail!) by redesigning it to be as innocuous and unnoticeable as possible.

My workshops do this refactoring by pushing participants to

Progressively trim down the scale and cost of their experiments until they fit within budgets and authority structures that they have direct control of, then

Identify obstacles to immediately deploying the downscaled experiment and find ways to circumvent or remove those obstacles.

Every participant so far has been able to design at least one experiment that is both usefully informative and viably sneaky within the space of the workshop’s allotted time.

OP might find this approach helpful for dealing with fog in the road.

Coming up (more fog)

The fog of time: Episode 9 of my monthly discussion series on not-knowing is about futurity. We’ll talk about how futurity changes not-knowing by providing opportunities to learn about new actions and new outcomes, change our norms about value over time, and respond to changes in the relative scarcity of resources. Thursday, 21 September, 8-10pm CEST. More information and tickets here.

See you next time,

VT