Hello friends,

Tomorrow! Not-knowing salon #5: False advertising. My next Interintellect salon is about how we use “uncertainty” to mean many things depending on context. Sometimes this involves appropriating the word by using it in ways that do violence to its definition as unquantifiable not-knowing. During the salon, we’ll talk about situations where this happens and why appropriation provides false comfort. Thursday, 18 May, 8-10PM CET; on Zoom and open to all. More information and tickets here. Drop me a line if you want to join but the ticket price is an insurmountable barrier — I'll sort you out.

Overloading and appropriation

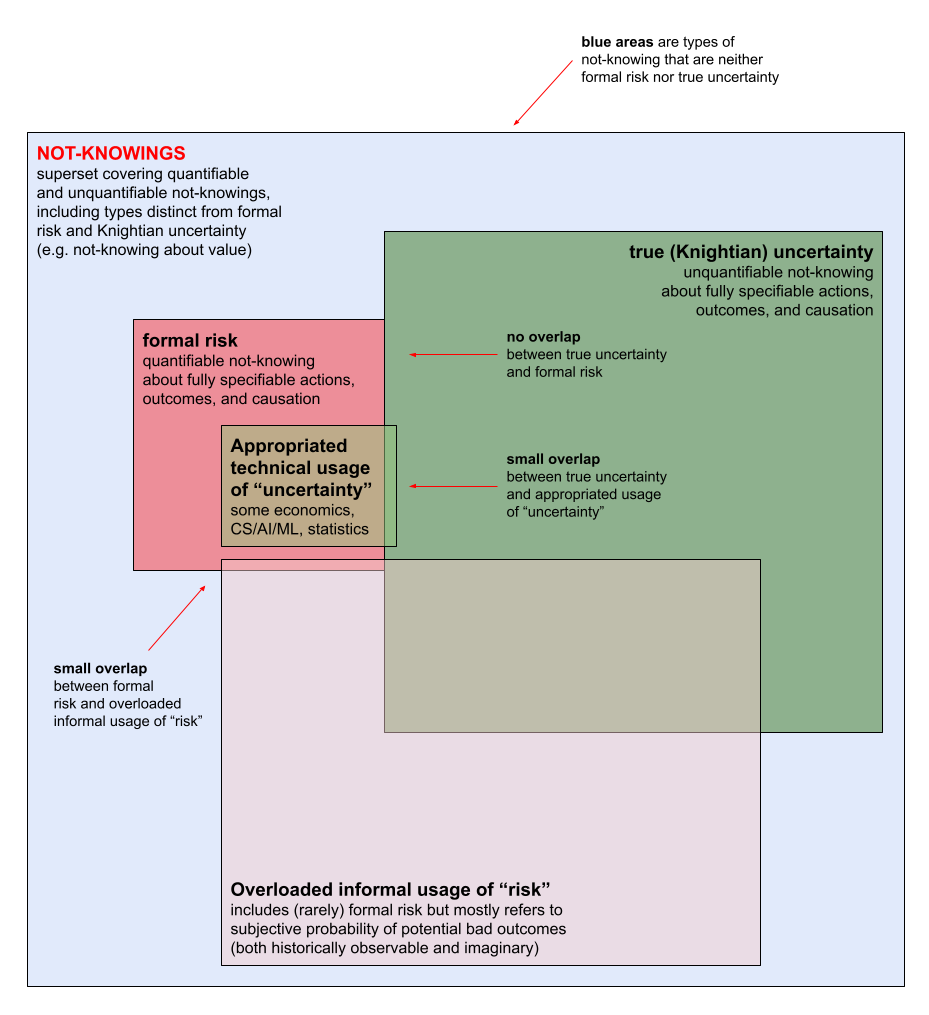

This essay is different from the ones that came before it in this series on aspects of not-knowing. The main difference is that I’m very actively still puzzling through and working out the ideas below. If you’re new to not-knowing (a concept different from both formal risk and from uncertainty), it might help to take a look at my introduction to not-knowing and the updated diagram below.

So far, a huge amount of trying to unpack not-knowing has been clearing the ground. By this I mean working out how we use words like “risk” or “uncertainty.” Turns out there are are least two types of inaccuracy in usage:

Overloading “risk”: Using “risk” to refer to many different situations of not-knowing, nearly all of which are not formal risk.

Appropriating “uncertainty”: Using “uncertainty” to imply a reference to Knightian uncertainty but actually referring to formal risk.

(🙏 Diana Kudayarova and Tse Wei Lim for helping me figure out that these two words are appropriate in the specific contexts they’re used in below.)

This is important because

[What we call something] → [What we think it is] → [How we choose to act on it] → [Outcomes]. More caveats

I’m not claiming expertise in computer science, economics, artificial intelligence, or statistics. If you are an expert in one of these fields and what I’ve written below seems wrong, please let me know. I’d especially appreciate it if you’d explain it to me in as simple and non-domain-specific language as possible. Write to me privately by email or in public on Twitter, Farcaster, or Bluesky — links all at the end.

I’m not claiming that every single technical usage of “uncertainty” in CS/AI/ML, economics, and psychology has appropriated the word in the sense I describe below. Some (often quite influential) approaches in these disciplines are doing this appropriation, but there are — there must be! — people using “uncertainty” in the correctly defined sense of the word.

I’m not claiming that the ideas presented below are correct and fixed. I’m still making up my mind and looking for new input.

Overloading “risk”

I’m using overloading in the same sense as in “function overloading” in software development, to mean a situation where different functions are all given the same name. This is what happens with the word “risk” in informal use. Nearly every real-world situation we call “risky” is actually a situation which isn’t formally risky. Instead it is a situation of non-risk not-knowing where formal risk conditions don't hold.

When we call a situation “risky,“ we act on the situation using methods that only work well when the conditions of formal risk apply — situations such as betting on the outcome of tossing a fair coin or throwing fair dice. (“Formal risk methods” are things like expected value analysis, cost-benefit analysis, etc.) When formal risk conditions don’t hold, formal risk methods for deciding how to act in the situation also don't work. This causes problems big and small, including mismanaging COVID-19 in the pandemic’s early days or the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

For a lot more detail on how we overload “risk,” how easily formal risk methods sneak into our thinking about “risky” situations, and why this is a problem, check out this essay on how to think more clearly about risk, this essay on the insidiousness of the formal risk methods, and the summary of the fourth discussion session on not-knowing.

Overloading “risk” means using “risk” (a word which should have a narrow meaning of “formal risk”) to also describe many situations of not-knowing that are not formally risky. Appropriating “uncertainty”

Important note: This is a work in progress. My criticisms of methods, conclusions, and syntheses below are provisional. I especially want to make this section better with the help of comments — so tell me where I’m wrong or need to be clearer!

For now I’m calling the second form of inaccuracy appropriated “uncertainty.”

“Appropriation” here means using the word “uncertainty” in a way that does violence to its meaning as unquantifiable not-knowing about a situation (i.e., Knight’s definition). Knight’s definition for “uncertainty” should prevail here because his definition is completely non-overlapping with the definition for “formal risk” — and non-overlapping definitions help get us to clarity.

For Knight, true uncertainty is not-knowing that is “not susceptible to measurement and hence to elimination.” True uncertainty is defined by the unquantifiability and unmanageability of not-knowing (as opposed to risk, which is not-knowing which can be quantified and thus managed and eliminated).

The appropriative strategy seems to be to use “uncertainty” to describe a form of not-knowing that can be quantified and thus can be made controllable. An example might illustrate what I mean by this.

Example: “Uncertainty” in machine learning (ML)

One ML task is to develop a machine model that can evaluate a set of data (e.g. a bunch of photos) and put labels on them (e.g. “this photo is of a mug,” “that photo is of a twig”) — an image classification model. The fewer the errors in the output (e.g. appending the label “this photo is of a mug” to a photo of a twig), the better the model.

Because the model is trained on some data (e.g. a dataset of images of mugs and twigs that has been labeled by a panel of humans) and then used on other, different data (images of things that could be mugs and twigs that need labeling), there can never be 100% certainty in a model’s labeling outputs.

When it comes to using a model, it’s important to know how much to trust the model’s outputs. This is particularly true if the outputs will be used to take actions that have important implications in the real world — such as an image classifier that is used by self-driving cars to detect and avoid traffic hazards. This model will have been trained on a dataset (say, of images of traffic hazards labeled by humans) and then used to label images taken from a self-driving car’s video camera. There won’t be 100% certainty in whether the model will correctly label a traffic hazard as “traffic hazard.”

In the ML context, this lack of 100% certainty would be labeled “uncertainty,” but what it actually seems to be is [not-knowing whether the model’s output is objectively correct or not, given a restricted range of assessments of correctness and strong assumptions about the similarities between training data and actual data being processed by the model].

This type of not-knowing doesn’t sound like either the narrow definition of formal risk or the overloaded informal definitions of risk, which may be why the AI/ML industry has decided to call it “uncertainty.” And this type of not-knowing about a model can be estimated and quantified (“uncertainty quantification”), thus permitting the model to be operationalised. One currently fashionable family of approaches for “quantifying uncertainty” in ML is conformal prediction, which “uses past experience to determine precise levels of confidence in new predictions.”

Here’s what it boils down to more generally: You don’t know something and you want a way to calculate how to take action despite not knowing that thing. In order for the calculation to work, you have to put a number on what you don’t know. One unfancy way to do this is to say “I’m making up a number.” The fancy way is to say: “I’ve developed a very sophisticated method for putting a number on what we don’t know so we can use our other very sophisticated methods for calculating what action to take.” These sophisticated methods for putting numbers on what is unknown are sometimes billed as methods for dealing with “uncertainty.”

This is not happening informally, but instead in highly technical contexts. AI/ML research is one such context, but similar dynamics in the usage of “uncertainty” also seem to be at work in economics and psychology.

Appropriating “uncertainty” means using “uncertainty” to mean many things that all imply aspects of true uncertainty, but which resolve, when you look closely at how those terms are defined either explicitly or implicitly in use, to forms of not-knowing that are so restricted that they essentially constitute formal risk.False comfort two ways

Both overloading and appropriation are appealing because they make us more comfortable.

Non-risk not-knowing (which includes true uncertainty) is scary because it isn’t quantifiable and cannot be managed away. Overloading means taking lots of very scary non-risk not-knowing and labeling it as “risk,” which is quantifiable and manageable. Very comforting.

Appropriation means taking specific and manageable types of not-knowing and labeling them as “uncertainty,” suggesting that true uncertainty is now manageable. Also very comforting.

The diagram at the beginning visualizes how overloading and appropriation sit in relation to other types of not-knowing.

Politics and the English language

The words we use to describe a situation of not-knowing shape how we think about acting in that situation. Both overloading and appropriation are bad because they warp how we think about acting when we face different forms of not-knowing.

If we say a situation is “risky” we tend to act using methods that are only appropriate for formal risk situations — this is bad when we use “risk” to refer to non-risk situations. Conversely, if we say a method is good for dealing with “uncertainty” we tend to think we can use it when faced with non-risk situations — this is bad when the method is actually only good for formal risk.

To me, this suggests that we need to say, as exactly as we can, what we mean when we are talking about the many different types of not-knowing that exist. The challenge is that our words for not-knowing — “risk,” “uncertainty,” “ignorance,” “ambiguity,” etc — are inadequate. The best word we have for non-risk not-knowing is Knight’s definition, and that isn’t perfect either because it contains many types of non-quantifiable not-knowing that are different from each other and omits some forms of non-risk not-knowing entirely (such as not-knowing about relative value).

This is why I’ve been using “not-knowing” instead as a blanket term to describe all the situations of partial knowledge we face. “Not-knowing” includes formal risk, true uncertainty, and forms of non-risk not-knowing that aren’t included in Knightian true uncertainty. I’ll be deep-diving into these different types of non-risk not-knowing in future salons and essays — my goal being to understand how each type differs in how you come to know it, relate to it, and deal with it.

Elsewhere, at other times

I wrote about the complicated affective/emotional backdrop for why it’s so hard to think clearly about not-knowing — or even to think about it at all.

A lot of what I’m doing now is trying to be as clear about words as possible and running into a lot of confusion. We seem to use them loosely (either accidentally or with specific intention to obfuscate). This looseness fucks up how we think, and then that fucks up how we act. It is always worth re-reading Orwell’s “Politics and the English language.”

A nice mention of my work on uncertainty and not-knowing (including idk) from Cedric at CommonCog, writing about how his recent highly personal experiment with accelerated learning under stress reveals the need for mental strength — and the connection between actively seeking out true uncertainty and building mental strength.

See you tomorrow if you’re joining for the salon discussion, or else right here in a couple of weeks.

Best,

VT

Love the terms of overloading and appropriating. I write software for a living, and it didn't strike me to use it outside of software.