The appreciation of rocks

and the detection and achievement of thing-coherence.

Hello friends,

A long one this week, about stones and walls and developing a sense for when something coheres (or doesn’t). But first, some ...

Announcements 📢

This Thursday 20/4 (tomorrow): Misnaming the beasts: April’s discussion in the monthly Interintellect series on not-knowing is about how the word “risk” is often misapplied to non-risk situations of not-knowing, and the dangers of misnaming the beasts like this. 8-10pm in Europe, on Zoom and open to all. As usual, drop me a line if you want to join but the ticket price is an insurmountable barrier — I'll sort you out. More information and tickets here, and the pre-reading is here.

Two podcast episodes:

On risk vs. not-knowing (10/4/2023), with Linus Lu from Interintellect. We spent a lot of time on how not-knowing is different from other approaches to partial knowledge, why it seems important enough to spend a chunk of time on it, and what we can do when faced with not-knowing. Listen to this podcast episode here.

On not-knowing, AI, and the future of marketing (31/3/2023), with Anna Kvasnevska and Irek Klimczak from GetResponse. We began by talking about the sudden rise of AI and how it makes the future of human work (especially in content and marketing) more uncertain. I found a way to squeeze in a discussion about why navigating not-knowing meaningfully is currently still the preserve of meat machines. Listen to this podcast episode here. Related: I also wrote about why meaning-making has become more important now that we have better machines to help us work.

The appreciation of rocks

Warning: This is actually about rocks 🪨

Recently, I took advantage of an empty spot in someone’s car to go up to Gordes to investigate rumours of a nice crusty little bar (and to do some other stuff too).

Gordes is officially one of The Most Beautiful Villages of France. With Bonnieux and Roussillon, it forms the Luberon’s Golden Triangle. This part of the south of France is the land of Casual Elegance. Money goes there to spend itself on real estate that intends to look old but nonetheless has modern conveniences.

One consequence of this kind of money sloshing about the Luberon is that building there is often done so that the result looks like what someone thinks traditional construction should look like. The constructions most visible from the road are stone walls. On the sides of houses, holding back terraces, dividing fields and vineyards.

So: It is important to disclose that I 💕 stone walls.

I first started looking out for them during a seminar at the Harvard Forest on anthropogenic landscape change. Stone walls are closely connected to the modern landscape of Massachusetts. Nowadays, Massachusetts is mostly forest, but the reforestation is relatively recent. In the 19th century, Massachusetts was nearly entirely covered in fields dedicated to agriculture. Because the state (and New England more broadly) is covered in the detritus from retreating glaciers, the soil is rocky.

How did New England become farmable? Settlers enclosed their fields and made them ploughable for farming through the same act: pulling rocks from the ground and making stone walls with them. When industrial farming made the Midwest more agriculturally viable, these fields were abandoned and the forests came back. Now, old stone walls interrupt nearly any Massachusetts forest walk.

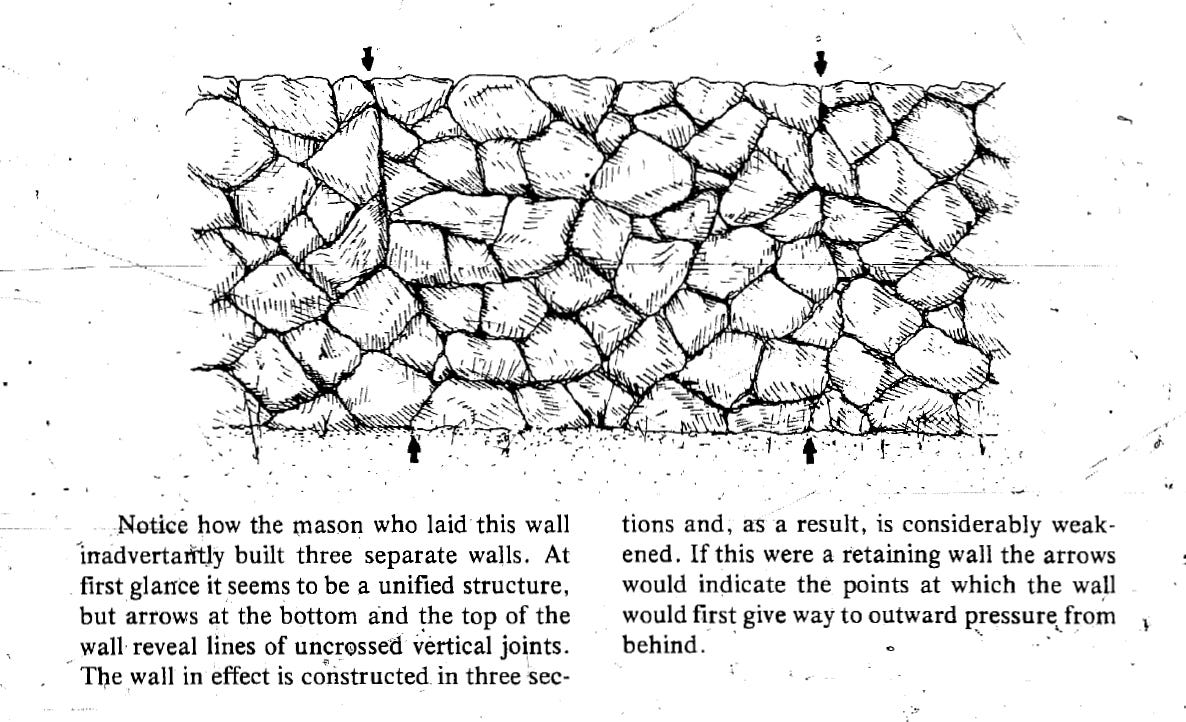

These New England stone walls were built simply, usually by dumping or cursorily stacking collected rocks in a linear pile. They all generally look right. By this, I mean that they look stable and as structurally sound as a pile of rocks. By comparison, the wall pictured below looks ... off. I saw this and many other similar walls on the drive north into the Luberon.

This wall looks and feels off in a way that is possibly only sub-consciously noticeable. The feeling of wrongness is connected to how it doesn’t look like a stable, structurally sound pile of rocks. This feeling is sub-conscious because most people who aren’t interested in actually building stone walls won’t have had any reason to explicitly articulate the reasons why most of that wall in Gordes doesn’t look like a pile of rocks but most of the wall pictured below does.

I lived for a few years in old stone houses — the house connected to the barn in the photo above, another in the mountains outside Le Puy (France’s lentil capital), and a third not far from Bonnieux in the Luberon. Over time, I formed a wish to also obtain for myself a small and dilapidated mountain shack requiring self-reconstruction. This is how I came upon The Owner-Builder's Guide to Stone Masonry.

The book articulates — brings into explicit conscious awareness — the reasons why piles of rock look the way they do. Imagine unloading a bunch of rocks from a truck. “As it is tossed to the ground observe how [each] stone lands. The first pieces thrown will hit the ground and roll until they come to rest on their natural base. Before long, the ground will be covered with pieces snuggled against one another. The pile then grows as more stones are cast onto it. They hit, bounce and finally settle on their natural bed. By the time your truck is unloaded, tossed stones will have created a stable pyramid. If this naturally formed pile is examined much will be learned about building with stone.” (That’s from page 41, in case you want to check it out yourself. The authors get extra points from me for using “snuggled” in a book about rocks.)

The logic of a pile of rocks gets unpacked a bit more.

In essence, there are two basic “rules” for making a pile (or wall) of stone which is stable and which looks stable: Stack stones so that 1) gravity acts as nearly vertically as possible on each stone in the pile, and 2) each stone in the pile rests fully and stably in an interlocking way on the stones below it.

The wall in Gordes was laid so that many of its component stones aren’t bedded securely on the stones directly below them. Behind is the reinforced concrete structure that actually holds up the building — the stones are only an ornamental veneer.

The Auvergne has many attractions for me, but a big one is that it has historically been too poor and badly connected to French centers of influence to attract the amount and type of money that wants and can afford an ornamental stone wall. The stone walls there were built back when there was no option to build for semblance. Most of the current residents and newcomers are not rich enough yet to routinely put up ornamental veneers.

When I became aware that the inner natures of some things were incoherent with their outward appearances, I started seeing this incoherence in many places.

Here, for instance, is the edge of a shelf in a shelving unit Habitat sells in France. The unit was on display in the shop window and caught my attention as I passed by because it looked ... off. Flimsy, like it was made of something less robust than the plywood from which it was constructed. (Plywood is very dimensionally stable and robust.)

When I went in to look more closely, it became clear that the whole thing was made of standard crappy particleboard under a thin veneer printed in stripes to look like medium-priced plywood. (Now that people understand that solid wood is too expensive for anything not exorbitant to be made from it, does applying a veneer that looks moderately priced make cheap particleboard furniture bizarrely more plausible and saleable?)

My working theory is that when a thing has an inside which is coherent with its outside, the whole behaves in ways that are consistent with each other. When I see and interact with these kinds of things, I register their consistency as a whole (even if sub-consciously). In contrast, when a thing has an inside which isn’t coherent with its outside, it behaves in ways which are inconsistent even if only barely. When I see and interact with these kinds of thing, I register the inconsistency and the whole reads as subtly, uncannily, but distinctly off.

Now, I want to step back and abstract away from stone and wood for a moment.

What I've been gradually coming to is the idea that we can begin from a sub-conscious sense that something is incoherent and eventually get to an articulated awareness of the reasons for that incoherence.

What drove this development for me in stone and wood was paying attention to when things feel off. This has also been happening with partial knowledge or, as I now call it, not-knowing.

I’m now more than a decade into trying to understand how we react when we face partial knowledge. When I started out in 2008, I was convinced that the most important thing was to recognise the difference between risk (quantifiable unknowns) and true/Knightian uncertainty (unquantifiable unknowns). I wanted to understand how people and teams behave differently when they explicitly recognise this difference. I wrote a book about this uncertainty mindset that came out in 2020, and still believe that first-order distinction is important to make.

But even as my first book crawled 🐛 towards publication in 2018 and 2019, looking at partial knowledge through just the one lens of risk vs true uncertainty had already started feeling ... off. I eventually started paying attention to this feeling and interrogating it hard during the Covid lockdowns.

Three years in, my current view is that Knight defined true uncertainty correctly. The problem is that his correct definition of true uncertainty is an unhelpfully enormous construct. It contains multitudes, and his definition barely suggests, let alone properly distinguishes between, the different types of unquantifiable unknowns that we face. So, while his definition is correct, it doesn’t help us figure out how to act in uncertainty.

I started using the clunky term “not-knowing” to guard against defaulting to previous categorisations of partial knowledge such as risk (both overused and misused) or true uncertainty (unhelpfully broad).

For me, there are many varieties of not-knowing. Formal risk is one type of not-knowing. Other types include not knowing about actions, not knowing about outcomes, not knowing about causation, and not knowing about value. There may be yet others. What is already clear is that each type of not-knowing poses a different challenge of understanding and invites a different relationship to action.

The lens of not-knowing allows both a more inclusive way to think about partial knowledge and a more precise one. Not-knowing is a reminder that partial knowledge is a category with variety, and specificity about type is important.

That an approach like this might be valuable is not a new idea. In 1988, the economics Nobel laureate Gary Becker said, “What will the situation be like in twenty years? Maybe somebody will come along with a more general and powerful theory, which includes rational choice as a special case, and that will have different behavioral implications in some of these intractable areas.” 🤞 the lens of not-knowing is a step in this direction. Time will tell.

With materials like stone and wood, recognising when a thing feels incoherent is a prerequisite for learning how to make a thing that feels coherent. After that, much active effort still needs to invested in developing the articulated awareness that allows that coherence to be built.

Intuition suggests that the same will be true for not-knowing.

Crass commercialism 💰: If you want to explore your relationship to not-knowing, the monthly Interintellect discussion series might be just the thing ...

Writing, recent and not-so-recent

More about not-knowing. I’ve been writing short essays about aspects of not-knowing, publishing as they come and revising them when they need it. Here is an overview of the research project. It's connected to the Interintellect series on not-knowing, but is not quite the same thing.

A time for rocks. My appreciation for rocks revived when I moved from London to a remote hamlet in the volcanically stony Auvergnat mountains during Covid. I wrote an essay about the kind of work, very broadly speaking, that can maybe only be done when far from cities and the crowds that live there. (Before you ask: I did not choose the title the essay eventually ran with.)

Until next time,

VT

Sounds like you’re a prime candidate to read Christopher Alexander’s "The Nature of Order”. He knows a thing or two about feeling wholeness… and has a thing for stone walls and vernacular architecture, too.