#23: Undeniable uncertainty

The band-aid comes off. How businesses should respond to unavoidable uncertainty. And a new, sporadic distraction from Equal Parts Eddie.

I’m an author, organizational sociologist, strategy professor, unsuccessful furniture maker, and Xoogler—this is yet another attempt to make sense of not-knowing.

I’ve been out of the apartment six times in the last 15 days.

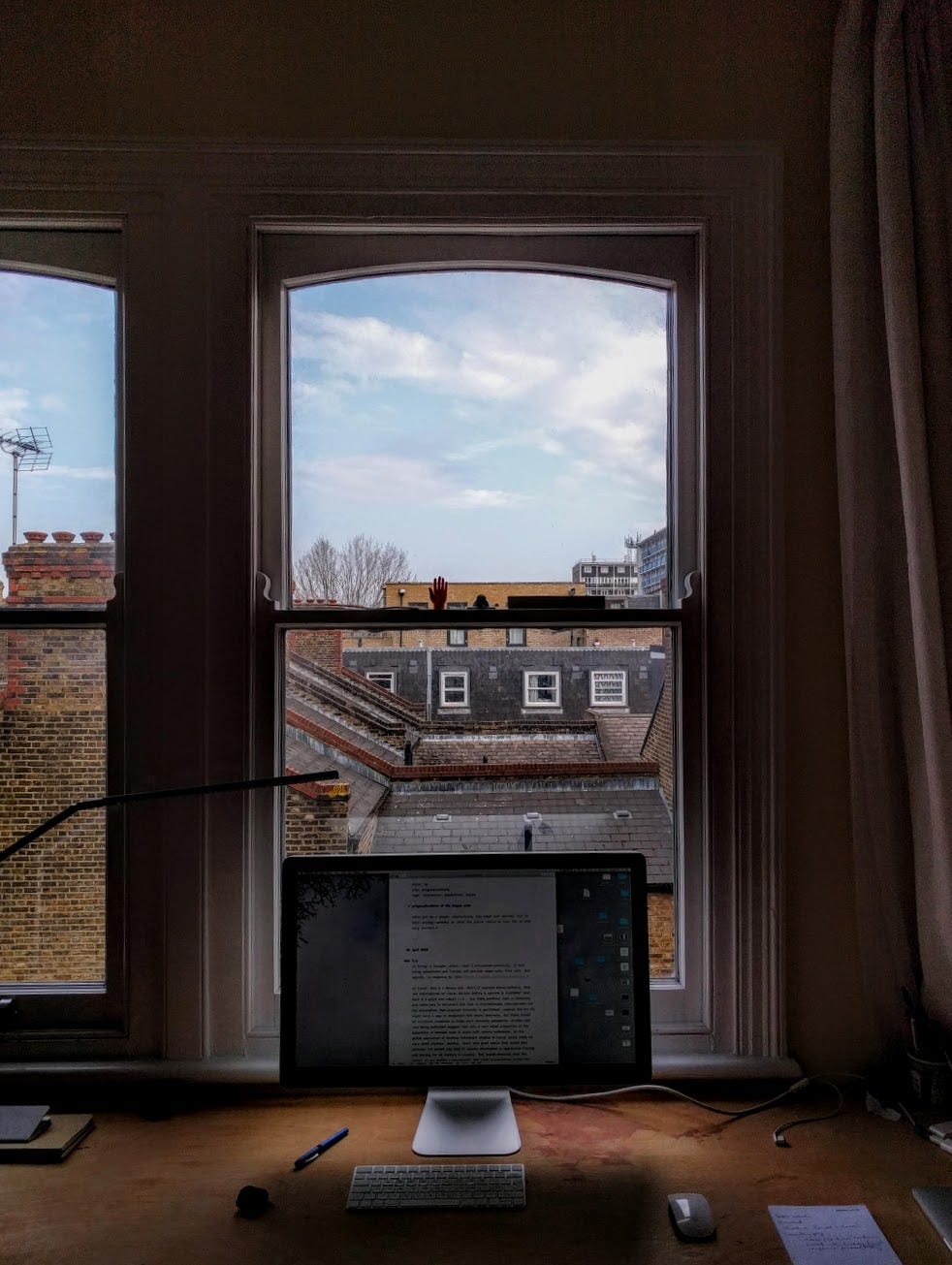

For much of these two weeks, London’s weather has been cold and blustery but mostly clear. I’m working off a large piece of plywood on trestles, facing two large and poorly insulated north-facing windows. It’s been nice to look out at trees in sunshine getting whipped about by the wind. I’m cooking even more than I used to. Getting enough sleep has been a snap. On a Zoom call (truly the new normal) with a collaborator temporarily hiding out in Devon a few days ago, I said, “it feels almost … idyllic.”

Then I felt abashed, because the world’s been plunged into a state of true uncertainty since the middle of March. Around then, the coronavirus penny finally dropped in the US and Europe; country after country locked itself down to temporarily slow the spread of coronavirus.

But it may give the wrong impression to say “plunged,” because that implies that this global coronavirus uncertainty is new as of the last few weeks. In fact, uncertainty from coronavirus has been latent since the first (currently unknown) crossing over between the virus’s usual animal hosts and intermediaries and the first human to be infected—but it wasn’t detected and recognized immediately.

Coronavirus uncertainty only became apparent to Chinese doctors in Wuhan who saw the first few cases of then-unknown viral pneumonia last December. It became apparent and undeniable to the Chinese state this January, when cases began to proliferate to the point where Wuhan had to be locked down. And it has only recently become apparent and undeniable to the general public and to governments worldwide.

There has been, in other words, a gradually widening circle of awareness of uncertainty.

Uncertainty is omnipresent—more so now that the world is so complex and interdependent. But while uncertainty may lurk in the background, it isn’t always apparent or even perceivable. When uncertainty isn’t readily apparent, it’s easy to be lulled into a false sense that things won’t change.

Preparing for unpredictable change requires adaptability, which comes from having spare or easily redeployable resources. A big cash buffer allows a business to invest in expensive re-tooling when its products are hit by unexpected regulation. Employees cross-trained in many functions can easily take up the slack when their sales colleagues get stuck in bad weather coming back from a tradeshow.

I’ve repeatedly emphasized how preparations for uncertainty invariably look pretty dumb during good (read: stable, predictable) times. As I wrote in issue #8, “preparing for uncertainty looks hare-brained, wasteful, and inefficient.” So people who insist on maximizing profitability during stable times usually succeed in slowly grinding adaptability out of a business because it looks like inefficiency.

The result is a super lean business highly adapted to a specific set of conditions. The cash buffer gets tied up in investments or acquisitions, the expensive cross-trained employees are replaced by outsourced workers. And if there’s a sudden and dramatic change to the specific conditions to which that super lean business is adapted, it no longer has the flexibility to respond.

This is also how the emergency field hospitals and pandemic stockpile get de-funded, the low-cost emergency ventilators get not-built (the illustration above is by the very excellent @lunchbreath), etc.

There’s a saying about putting all the eggs in the same basket which may apply here.

A lot of modern management best practice ends up being about maximizing efficiency. Our cultural and organizational memory seems to be especially bad at remembering why we should invest in apparently inefficient, wasteful resources that give us the ability to be flexible and adaptable when we need to be.

This may be why many businesses seem to have been caught out by being suddenly exposed to the undeniable, unavoidable uncertainty of the environment—what, in issue #13, I described as an involuntary revelation of the nature of reality.

The immediate business impact of coronavirus seems to hit industries differently. For most non-retail and non-production industries—the world of white-collar work—the biggest challenges seem to be in transforming work that happens in an office to work that happens entirely at home. (Much less straightforward than it appears.)

It’s worse in the world of actual things. Revenues have dried up for brick and mortar non-essential retail. And the travel and hospitality industries have been devastated even in the first weeks of lockdown. They make money by moving people around and bringing people together—coronavirus will make both difficult or impossible for many months, if not a year or more.

Things can only plausibly start to return to normal with effective, nearly ubiquitous testing for coronavirus infection and immunity. A real return to normal seems only possible when a vaccine is widely available. Based on the best current knowledge, widespread testing isn’t really plausible for the next few months, and the best-case scenario is a vaccine in 18-24 months. Businesses are probably going to be experiencing this great uncertainty until then.

Obviously, it would be ideal to have spare or flexible resources waiting when uncertainty becomes unavoidably apparent. But the businesses which don’t have these should act anyway.

Here are four principles for responding to uncertain situations:

Take small but immediate actions that are designed to limit commitment while allowing exploration of the changing situation. Businesses shouldn’t wait to make big, irrevocable moves. Instead they should make lots of small, fast, low-cost, uncomfortable moves that let them experiment, explore, and learn about what is happening. For more on progressively overloading an organization to drive learning, see issue #10)

Don’t wait for validated strategies to become available before taking action. Coronavirus poses a challenge for businesses which is literally unprecedented in nature and impact. Moreover, the situation itself is emergent, changing with every passing hour and day. For these reasons, no business will have access to a tried-and-tested playbook for responding to coronavirus—and so businesses shouldn’t wait for these to become available before acting.

Don’t try to apply risk mindset to optimize actions. Trying to figure out the best possible set of actions to take implies knowing all the possible actions that can be taken. When knowledge is imperfect (as it is now), risk mindset stifles a business’s ability to develop unconventional responses (for more on reality mining and pragmatic imagination, see issue #3). Risk mindset is inappropriate in situations of uncertainty, and may be fatal (on which, see issue #21).

Invest time and effort to immediately understand and clearly articulate not only what goals are prioritized but also what tradeoffs should be made to achieve those goals. When the situation is rapidly evolving and rapid distributed action is essential, clarity about goals and acceptable tradeoffs (for more on tradeoffs, see issue #9) becomes even more important for enabling employees to act effectively and autonomously. For more on Boris, a method for understanding and articulating goals and tradeoffs across teams and organizations, see issue #17).

Department of Sporadic Distractions: Introducing … Equal Parts Eddie’s Coronavirus Cocktail Corner

I’ve known Equal Parts Eddie, globetrotting drinks industry éminence grise, for lo, these many years, in which time he’s guided me to some very delicious beverages. His identity is disguised to protect the innocent and insufficiently alert. Now, hear his (lightly edited) voice:

Gin and tonic—the ultimate marriage of convenience. Juniper for the stomach, quinine for the bugs, lime for the scurvy. But the cocktail canon holds so much more: gin sours, gin punches, and gin mixed with every sort of aromatized wine, most notably vermouth.

“But I’m at home! I’m not a bartender! And I’m certainly not a mixologist!”, you cry. No worries. Neither is Equal Parts Eddie. A glug of this, a glug of that, some ice, you’re done. Back to your Zoom call.

But, what glug to glug? If your home bar is filled with classic gins (the names you knew growing up), they’ll be juniper-y, giving an oleaginous, flatly spicy character in the middle or middle-back of your tongue. That’s right: well-distilled juniper doesn’t taste like pine! The herbal character of a good vermouth will mostly stimulate the front of your tongue. Mix the two together—Equal Parts, natch—and you get a sort of balance across the palate. Look for a slightly sweet French blanc vermouth. (And save the dry vermouth for your martini.)

But modern gins now abound and maybe you have some. What then? Equal Parts Eddie has been doing some ... experiments, and here’s what he’s found:

Most new gins are floral or herbal. But vermouth is floral and herbal, due to the required presence of wormwood. That’s just way too much of the same thing. Don’t mix your modern gins with vermouth. So what other kind of aromatized wine can be that second glug? Lots of these newfangled gins are a little astringent, or maybe just a bit coarse, due to a funny botanical or maybe a dodgy tails cut. So your second glug should have a bit of sugar if you’re mixing it with a modern gin.

Equal Parts Eddie experimented, experimented, and experimented. What he kept coming back to, for these floral and herbal new gins, was quinquina. Wine and quinine. Where a classic gin and vermouth balances the hit across the back (juniper) and the front (wormwood) of the palate, a modern gin and quinquina achieves that balance in reverse: the quinine in quinquina hits the back palate, while the floral/herbal botanicals in the gin hit the front. Eddie’s choice is a white Corsican quinquina. (Always refrigerate your aromatized wines after opening; they’re wines, after all.)

Mixing gin with an aromatized wine is not scientifically proven and it’s not guaranteed to be perfect—but it’s a low-risk approach in these high-uncertainty times.

Signs

My first year in London, a coworker gave me a cutting from her rubber tree. Since then, it’s turned into an overgrown, glossy, dark green bush in my east-facing, well-lit, always slightly overheated room at the office. Pretty good growing conditions for a tropical plant.

The last day before my office closed down, I went in to take the rubber tree home to my frosty apartment. Some weeks later, most of its leaves have either yellowed or fallen off.

If you found this useful or thought-provoking, you should definitely share it indiscriminately with masses of people. You can find previous issues of The Uncertainty Mindset here. I’m on the web at www.vaughntan.org, on Twitter @vaughn_tan, Instagram @vaughn.tan, or by email at <uncertaintymindset@vaughntan.org>.