Human mRNA

An old-school tool for unexpected connections.

This issue is about people who seek out connections that should exist but don’t, and who translate and move information around silo-ed organisations and ecosystems to make those connections happen — I call them human mRNA.

But first, some crass commercialism.

Neither here nor there

We’re now midway through my Interintellect series on not-knowing. This part of the series explores four areas where not-knowing can arise: actions, outcomes (both in session 6), causation (session 7), and values (session 8).

I started this series (and the project on not-knowing) from a belief that our ways of understanding what we don’t know are too crude, and that unsophistication makes us miss many opportunities. (Here’s an introduction to not-knowing, and an explanation of why I’m spending time on not-knowing.) Halfway through the series, I’m even more convinced that better thinking about not-knowing will let us build a healthier relationship with it and develop a more sophisticated toolkit for taking smarter actions when faced with it (we’ll get there in sessions 11-13).

Discussion participants say nice things like “this was the highest value 2 hours in recent memory,” and “I have wanted to have conversations like these for a long time, so it’s quite incredible to be in the company of people asking big questions along these lines.” So join us for whichever sessions appeal — you don’t have to come for the whole series and you can look at the summaries of previous sessions here). If you want to join but the ticket price is unmanageable, let me know and I’ll sort you out.

Session 7: Connecting Actions and Results (Tues, 25/7). Making good strategy is hard when you don’t know how particular actions are connected to particular outcomes — in other words, when there is causal not-knowing. On July 25, we’ll be discussing five ways we could not-know about causation (illustrated below), and how each way offers different constraints and opportunities for strategy. More information + tickets, and a short essay about causal not-knowing.

Session 8: What Results Are Worth (Thurs, 17/8). Not-knowing about values makes it hard to compare desired outcomes and to choose actions. At the same time, not-knowing about values creates space for new ideas of what should be valuable — which is how stuff like art, cryptocurrency, and the end of legalised slavery can happen. On August 17, we’ll discuss how not-knowing about values offers different opportunities for strategy and creates space for new futures. More information + tickets, with the pre-reading coming soon 🤞.

Human mRNA

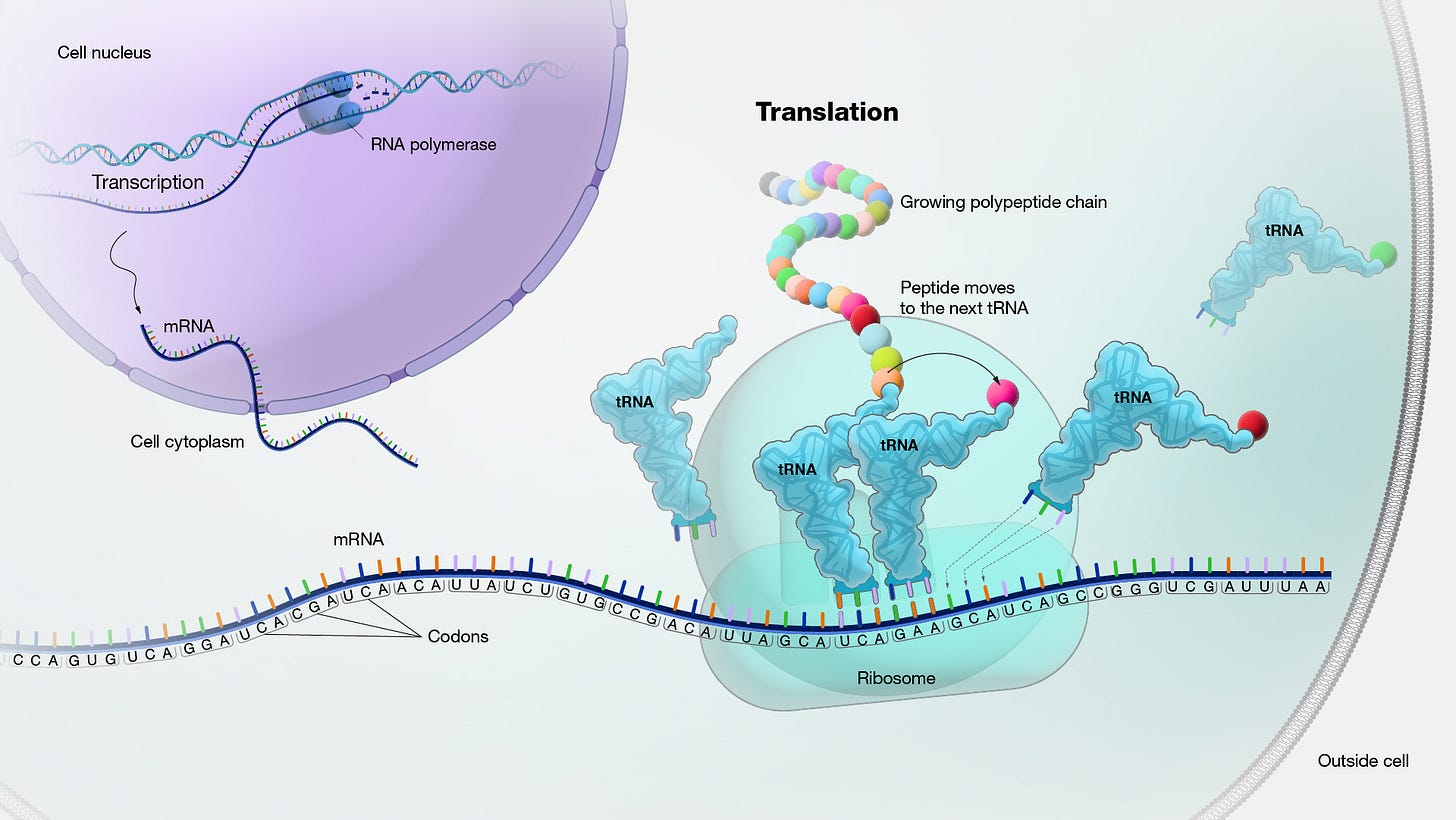

When I worked at Google literally decades ago (😱) I noticed something which I now call human mRNA — human analogues of the messenger RNA that does the vital work of moving genetic information around inside cells and translating it into a form that can be used for protein synthesis.

Gerry was human mRNA. Gerry’s “real” job (name changed to protect the innocent) was in the technical writing team, but he would show up at a staff meeting for the Geo products data and legal team, in a biweekly lunch group of bioinformaticians, huddled in a cube with a bunch of engineers working on infrastructure for collaboration products, at a Friday afternoon party with a pod from the Ads inside sales team. That kind of thing.

Each of Gerry’s groups was far removed from the others, and not just in the sense that they were in different buildings on campus. They were contexts which were conceptually far apart: they worked on different things and in different ways. Gerry somehow was welcomed as an insider in each context. And he often brought some useful piece of information to each context that wouldn’t have been available otherwise — for instance, that the bioinformatics group had developed a repurposable storage infrastructure which solved a similar problem faced by the collaboration products engineers.

The information Gerry moved around formed connections that bridged gaps in Google’s internal structure of people and teams. Sociologists would say that Gerry bridged structural holes in the internal network. That image of static, unmoving bridges over chasms makes it seem as if anyone who shows up periodically in otherwise disconnected teams can become a good conduit for information to flow from one place to another. This is a version of the too-seductive idea that even accidental meetings (such as conversations at the proverbial water cooler) can help connect organisations internally and dramatically increase innovation. Accidental meetings are better than none at all, but this shallow reading misses most of what’s actually going on.

Here’s my view of what was happening: Gerry was invaluable as an information conduit because he made it possible to see and absorb information that was would otherwise be hidden in plain sight.

Over time, every group — formal or informal; anywhere, not just at Google — inevitably develops an internal language and system of meaning which outsiders find hard to fully understand. This is part of the emergence of group culture and is how groups hide information from outsiders without meaning to, or even when they’re working hard to share it with others.

Gerry made this hidden information available because he “spoke” the internal languages of both the collaboration products engineers and the bioinformaticians. Speaking both languages allowed him to see that storage infrastructure built in one context could solve a problem in the other context. He understood the meanings of the problem and solution in both contexts, and could translate those meanings from one (internal) language to the other.

Bridging structural holes is about being an effective information conduit. An information conduit shouldn’t just be a static bridge between source and recipient — to be effective, it must also translate the information into a form that is meaningfully useful for the recipient. (Imagine, for instance, how useful it would be to send a refrigerator servicing manual written in Mandarin to a technician who can only read in English.) Translation is particular important when information is trying to move across a big or poorly understood gap in contexts, which is also when it is most likely to be simultaneously new and useful in context.

Knowledge management systems and other technology-first solutions for increasing this kind of internal connectivity are always well-intended. But they invariably fail at the translation part of the job because good translation is fundamentally about meaning-making.

I’ve written before about the difficulty and importance of meaning-making in translation. Humans are capricious and unreliable, but they’re the only ones who can do the work of translating meaning across contexts because making meaning is ultimate a uniquely human capability. In some form or other, humans have always translated meaning across contexts. It rarely gets named and examined, so I call it human mRNA work to call attention to the fact that it is work and that it can really only be done by humans for now. Humans are still the best way to build effective information conduits between distant contexts.

Where human mRNA work is encouraged and supported, it creates environments where ideas (or people/teams/companies) meet when they should … especially when it isn’t obvious that they should meet. Whatever name you give human mRNA work, supporting it intentionally is vital for building innovative companies and ecosystems.

At Google, human mRNA work got little credit or support. I knew a handful of Gerrys at Google. They drew connections between people and projects, useful connections which should have existed but didn’t until a Gerry came along and made the connection happen. This valuable work was always informal and rarely recognised as part of their “real” jobs — sometimes, they were even penalised for doing it.

Google didn’t design itself to encourage human mRNA work but it’s cheap and easy to design systems that identify people who are good at doing human mRNA work, and encourage them to do more of it. Why aren’t more leaders, planners, and policymakers doing this?

(This article is also posted on my website.)

This and that

Stuff with me, from me, and from other people.

I join the Evolving Leader podcast for an episode on uncertainty and not-knowing (45 min). We talked about why it’s easy (and dangerous) to mix up risk and uncertainty, why it's so hard for leaders to admit to being uncertain, how to train for better uncertainty tolerance and productive discomfort, how desperation by design works, and what the future of work might look like given the rise of AI.

I wrote two new short explainers in the series of essays unpacking aspects of not-knowing: one about different sources of not-knowing about causation, and another about different sources of not-knowing for actions and outcomes. Why bother unpacking different sources of not-knowing? Because they call for different approaches to resolution and offer different opportunities for strategy.

Eugene Wei suggests that Twitter’s light is fading under the fog of a kind of search problem.

A paper about “proxy failure,” which is what happens when metrics stop being good measures when they become targets.

Avery Pennarun writes about the idea of financial debt, particular how and which parts can be extended metaphorically. A useful read next in context of the current kerfuffle about how British water companies are on the verge of collapse due to fancy debt engineering.

A video about how Linotype casting machines work; part 1 and part 2. So good. Even if you are not a type and print nerd.

Matt Webb distinguishes between prompt engineering and prompt whispering in the context of interacting with LLMs. Engineering is a structured, legibilised form of whispering — and both are expressions of empirical/formal understanding of the LLM’s behaviour? My view is that both are differently sophisticated forms of meaning-making in the context of a new tool and framework for meaning. (Again we come back to the idea that when we think about human-AI interaction, the part that is irreducibly human is the creation and assignment of meaning to things.)

See you next time,

VT

> Knowledge management systems and other technology-first solutions for increasing this kind of internal connectivity are always well-intended. But they invariably fail at the translation part of the job because good translation is fundamentally about meaning-making

I perform some part of this for a singapore country unit of a F50 company

The SG entity hires me as vendor

But they don’t pay me for that. Officially I’m just there to write code and build systems.

But I wouldn’t have built anything usable if i didn’t play some aspect of meaning making across different contexts

The next phase of improvement I’m looking at is to build a data dictionary so that some of the unnecessary (in my opinion) inconsistency in terms can be removed

As someone whose value in corporate settings has always mostly been as Human mRNA, I've had a couple of bosses who understood/valued it and others who didn't. What's frustrating is that every so many years someone writes about this and nothing changes - thus even when teams have someone like this, they are so often lost in a re-org because they aren't seen/valued.