Organizational technology for uncertainty work

Or: The importance of mundane organizational processes.

Hello friends,

I’m just back from the Bay Area where I gave a talk at Stripe on organizational design as a key (but often-overlooked) technology for strategy. This is particularly important for businesses that want to innovate, or that work in rapidly and unpredictably changing industries — in other words, organizations that are committed to doing uncertainty work. As always, if you find this newsletter useful, you shouldn’t hesitate to “Like” it or share it with others.

tl;dr: Designing organizations adapted to uncertainty work is strategically important. This issue talks about 3 aspects of organizational design for uncertainty work:

Uncertainty work ≠ risk work. Uncertainty work (new product development, R&D, innovation, new business models) requires a fundamentally different approach to organizational design;

Mundane organizational processes literally shape organizations by shaping everyday organizational life.

Appropriate organizational technology requires redesigning these mundane organizational processes to explicitly acknowledge uncertainty.

Organization as a technology

How we choose to organize a group of people determines how well they are able to work: our choices in designing organizations can be strategic. Organization becomes a strategic technology when the approach to organizing is intentionally chosen to be appropriate for the type of work to be done. The main obstacle to being strategic about organizational technology is accidentally designing the organization for risk work when it needs to do uncertainty work.

Uncertainty work ≠ risk work

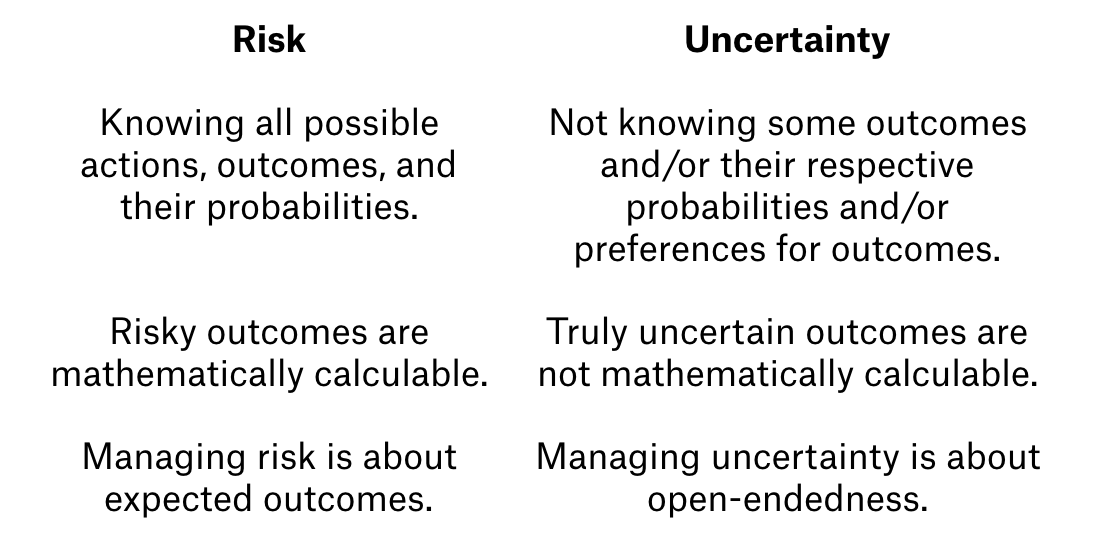

Both risk and uncertainty are situations of partial knowledge: not-knowing exactly what happens in the future. “Risk” and “uncertainty” are often used interchangeably but they are fundamentally different.

In a risky situation, all possible actions, outcomes, and their respective probabilities are known. The outcomes of risky situations are therefore mathematically calculable (using long-established methods from statistics and probability). Managing risk is about expected outcomes (using expected value and cost-benefit analyses). True risk situations are rare outside of carefully constructed games of chance like throwing fair dice or tossing fair coins.

In a truly uncertain situation, actions, outcomes, their respective probabilities, or even preferences for outcomes are incompletely known. This makes the outcomes of truly uncertain situations not mathematically calculable. Managing uncertainty is about learning to deal with open-endedness.

All work that organizations do can be divided into two conceptual categories along these lines.

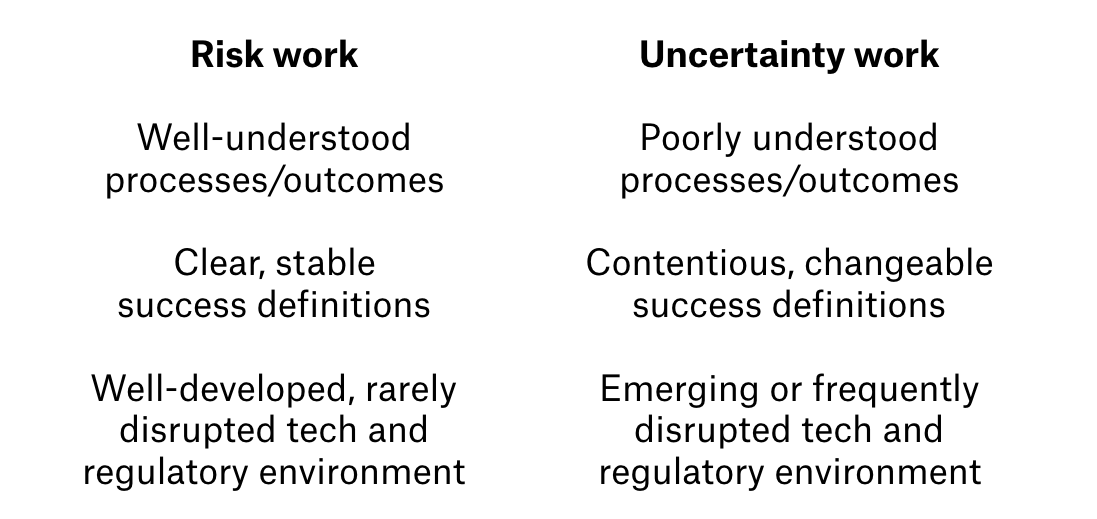

Risk work is about well-understood processes and outcomes and clear, stable definitions of success. It often happens in highly developed, rarely disrupted technology and regulatory environments.

Uncertainty work involves poorly understood or emergent processes and outcomes. The definition of success is often in contention and changes frequently. The technology and regulatory environment changes frequently and unexpectedly. Organizations need to do both risk work and uncertainty work to survive and succeed, but the two are fundamentally different.

All innovation falls into the realm of uncertainty work — this includes developing new products, new processes, and new business models, all types of research and development, and ventures into new markets.

Uncertainty work generates a huge amount of value and competitive advantage. Designing organizations to do uncertainty work well is both desirable and essential — but it’s easy to accidentally design an organization in ways that impede uncertainty work.

Mundane decisions literally shape organizations

This is because organization design happens by shaping the everyday things that people and teams in the organization do. Mundane processes determine these everyday things: who gets hired, what goals employees and groups pursue, how employees are motivated. Yet, organizations usually rely on “industry best practices” for their recruitment and hiring processes, goal-setting processes, and incentive structures.

This is a problem for the organization that needs or wants to do uncertainty work because these best practices often secretly embed risk assumptions. Best practices nearly always assume that the work that needs to be done and the definition of success won’t change, and that the environment is stable. This is why hiring processes call for stable, clearly defined job descriptions, goal-setting processes are focused on setting concrete and measurable goals, and incentive systems are designed around achieving predefined milestones.

These may be best practices for risk work, but they are inappropriate for uncertainty work. Any organization — big or small, for-profit or not — that needs (or wants) to do uncertainty work needs to have the appropriate organizational technology.

Appropriate organizational technology for uncertainty work

Paying attention to mundane processes allows them to be thoughtfully redesigned to be appropriate for uncertainty work. At base, this simply requires explicitly acknowledging that the organization faces uncertainty, not just risk.

This single mindset change — from an unexamined risk mindset to an explicit uncertainty mindset — is what allows mundane organizational processes to be seriously considered and updated.

Hiring: Instead of designing job roles to be stable and clearly defined, make them open-ended and changeable and combine these open-ended roles with processes for continually negotiating and updating job roles over time.

Goal-setting: Instead of focusing on setting only concrete and measurable goals, work on agreeing on criteria for recognising success and on the acceptable (and unacceptable) tradeoffs that can be made.

Motivation: Instead of incentivising people and teams instrumentally to achieve only predefined milestones, use desperation by design to create conditions under which they are driven to learn new skills and ways of working.

These alternative ways of approaching hiring, goal-setting, and motivation may sound impractical and ethereal, but I assure you that they are all concrete, practical, and doable. I’ll write more about redesigning hiring, goal-setting, and motivation processes for uncertainty work in the next few weeks.

If you can’t wait, I explain them in detail with examples in parts 4-6 of The Uncertainty Mindset.

Coming up

Thursday, Oct 19: Episode 10 of my monthly discussion series is about how the four types of not-knowing (about actions and outcomes, causation, and values) reverberate back and forth between each other over time. The approaches and tools of not-knowing must do their best to accommodate how a change in one of the four affects the others. So, in this episode we’ll talk about why relating well to not-knowing requires:

A mindset that is reflexive and flexible.

Broad approaches to action that expect change and evolution.

Tools that look very different from risk-management tools.

More information and tickets available here.

See you here soon,

VT