Fallacy lens (wk 27/2025)

Optimisation as fallacy; business as meaning-making act; the drudgery of administration; the search for good manufacture; working in a canicule.

Hello friends,

This week, France has turned to a leathery and exhausted crisp while gripped by a monstrous Europe-wide heat wave. I’m now back in France until July 26 to deliver a few pieces of work and continue the apparently unending process of fixing up the apartment — will be between Ljubljana (15-18), Paris (21-24), and Marseille (the rest of the time). Drop me a line if you’re in any of those places and want to get a coffee or, supply permitting, a glass of wine.

Midweek, I started gathering tax documentation for the small consulting company I work through. It’s already taken over 15 hours of sorting through three email accounts and folders of receipt photos, invoices, bank statements, and other miscellaneous digital bits and pieces. I’ve not even started on the paper receipts that I put into a series of boxes to deal with later (= now).

Is this is the moment I finally move to using some kind of application or service that will a) send invoices in multiple currencies with live historical conversion rates, b) do automatic bookkeeping and reimbursements from machine-processed receipt submissions, all at a price reasonable for a business with a two-person headcount (for now). Do you have a solution you’re happy with? Drop me a line as this inquiring mind would like to know.

Writing

I wrote two short pieces this week.

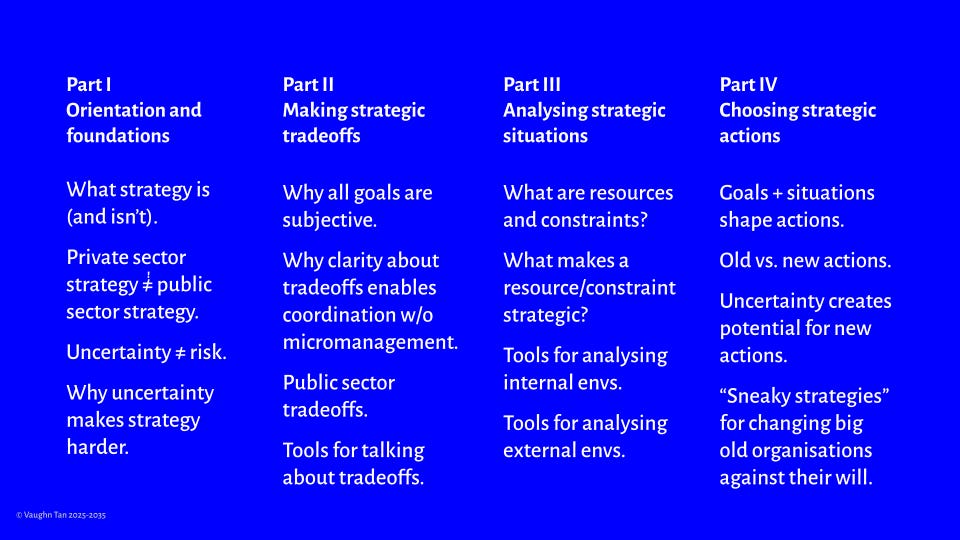

As many of you probably know, I’ve spent nearly two decades trying to unpack the surprisingly textured and poorly understood concept of uncertainty, and develop some kind of useful set of practices for dealing with different types of non-risk uncertainty. Understanding the difference between uncertainty and risk is central to being able to respond properly to an increasingly uncertain, not simply risky, world.

A futurist friend recently made an expensive, early exit from the Middle East during a flare-up in the Israel-Iran conflict ... then felt embarrassed when the situation de-escalated. That embarrassment stems from misframing the decision as an optimisation problem — which assumes that precise estimation of risks, probabilities, and timings is possible. It wasn’t. The situation wasn’t only risky, it was also uncertain — marked by capricious actors uninterested in playing by well-understood rules. In uncertain situations, optimisation fails and other frames for decisionmaking make much more sense. The real skill here is correctly diagnosing the type of not-knowing you’re facing, then choosing a reasoned and appropriate decision frame instead of defaulting to a decision frame only suited to risk.

👉 Read more here about why optimisation is the wrong decision frame for uncertain situations.In the last few years, I’ve developed a language around four different types of not-knowing that aren’t risky. The most important type is also the least understood and discussed: Not-knowing about relative value. This is the form of uncertainty that underlies the writing I’ve been doing over the last 18 months on meaning-making as a lens for considering AI.

Anthropic’s experiment with using Claude as an autonomous shopkeeper agent failed — not just because the AI was gullible, but because running even a simple business involves inherently human, meaning-making decisions. Doing business isn’t just executing tasks like pricing or inventory. It’s deciding what matters, what to trade off, and what success looks like. These are subjective choices without correct answers. Until AI systems can make meaning, they shouldn’t be tasked with running businesses on their own. The real question isn’t whether an AI is gullible, but whether the work requires meaning-making. If it does, that work must remain human.

👉 Read more here about why doing business is a meaning-making act. Elsewhere

Lufthansa seems to have lost one of my bags, prompting a low-level search for replacement clothing for next week. Can I really be the only person who wants a small collection of relatively basic normal-person clothing that a) isn’t technical clothing, workwear, or athleisure, b) is made not by a MegaCorp, c) uses well-sourced material and fabrication techniques, c) has interesting but not outlandish cuts that are actually wearable in a wide range of settings not just at a vernissage, d) is designed around normal washing instead of drycleaning or other forms of specialist clothing care. Why is it so hard to find such things outside of bespoke?

I canvassed the small number of clothing industry experts I know. Below are some of the recommendations that came back which seemed especially good to me, but only a few met the full brief — especially, workwear seems nearly inescapable.

And the consensus opinion (mine included) is that some items from MegaCorps are okay because the alternatives from non-MegaCorps are better but not enough to justify the massive price difference (e.g., t-shirts from James Perse). Drop me a line if you know of a maker I should look at.

See you next week,

VT