"Good" questions

What foundationality means for questions, why it matters, and how it applies to AI.

Hello friends,

tl;dr: Getting useful answers depends on asking good questions, and foundationality is a key criterion in determining whether a question is “good.” A question is more foundational when its answer affects more other questions. This is why breakthroughs are more likely when we spend the time and effort to figure out how to articulate a question in a way that is more foundational.

This month, I’ve been spending my time building training programs to help clients’ employees get comfy with uncertainty (not just risk). But most of my headspace has been occupied by an AI conference I’ve been retained to help convene.

The conference’s goal is to articulate foundational AI questions that will stimulate emergent yet coordinated activity to answer those questions. This raises issues that apply to good strategy in general. I’ve unpacked some of them recently when writing about principles for designing good experiments and for framing problems well.

My general argument is that thinking clearly allows you to act more effectively. Asking “good” questions is essential for clear thinking (and the result of clear thinking). But what does it mean for a question to be “good”? One strong criterion is whether the question is foundational.

What is foundationality?

My view is that foundationality is a conceptual construct that is based on understanding that questions sit in a hierarchy of dependency. This diagram of a stack of stones illustrates the main intuition behind this definition.

The arrows show which stone/s each stone rests on. All the stones in the stack rest on the ones at the bottom. Stones that are further up the stack have fewer stones resting on them. In this way of interpreting the stack, C is the least-foundational stone because only the 3 stones above C tumble if it is moved, the ones below it are unaffected. B is more foundational (more stones depend on it than on C), and A is even more foundational than B or C.

(That image is from The Owner-Builder's Guide to Stone Masonry, which featured in a previous issue about rocks and how to appreciate them.)

Like stones in a wall, questions lie on top of each other conceptually. This is why questions can be said to be more (or less) foundational. A question is more foundational when its answer affects more other questions.

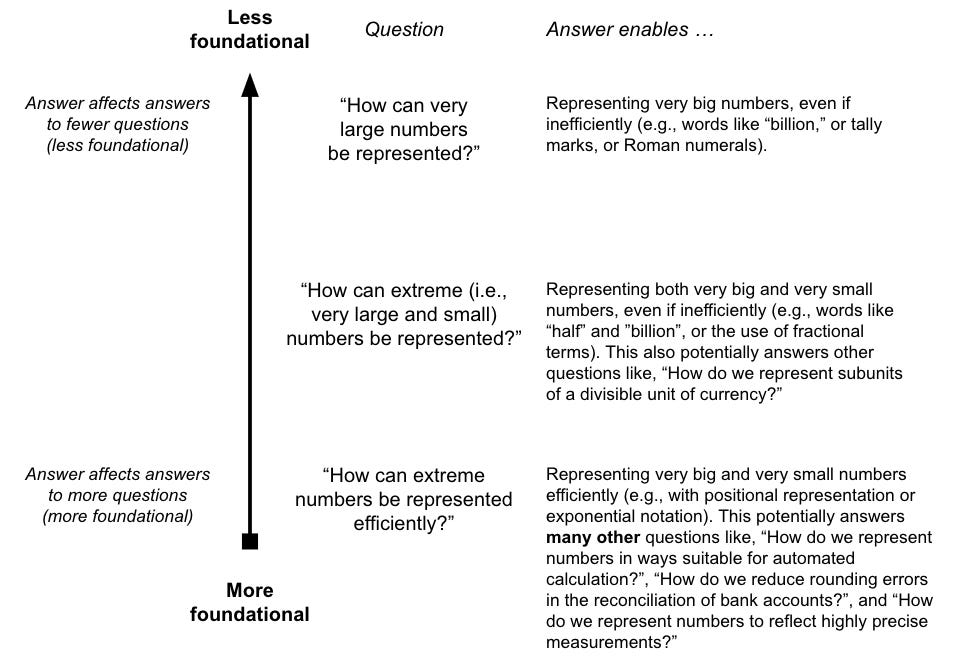

A concrete example of some already-answered questions at different levels of foundationality might help illustrate both what foundationality is and why it is important to consider.

Example: The question of number representation

Representing numbers is essential for manipulating and using them well, but what’s a “good” way of asking how to represent numbers?

Less-foundational question: “How can extremely large numbers be represented?” One possible answer is Roman numerals (where letters represent values; so C = 100, L = 50, X = 10 etc). This answer works but is inefficient (requires many Roman numerals for large numbers) and even more inefficient when it comes to representing very small numbers. This answer is thus inarguably useful but it answers relatively few other questions.

More-foundational question: “How can extreme numbers (i.e., extremely large and small) be represented?” One answer to this is to use words that are understood to have big and small values, like “billion,” or “half.” The answer to this more-foundational question has wider potential applicability. It’s now possible to represent both big and small numbers, and that makes it also possible to answer some other questions like “How do we represent the value of subdivided objects?” and thus “How do we represent the value of currency subunits?” But this answer isn’t very efficient; for one thing, it doesn’t generalise because specific words would be needed for every large and small number to be represented.

Even-more-foundational question: “How can extreme numbers be represented efficiently?” One answer to this is positional representation with a radix point, where the relative position of a digit denotes its value-multiple (e.g. the “9” in 965.7 represents 9 x 100, and the “7” represents 7 x 0.1). This answer is efficient because it uses relatively few glyphs and generalises to all rational numbers — the greater foundationality of this question framing calls forth an answer which is “better” than the answers that less-foundational framings of the question would call forth. Crucially, this answer makes it possible to also answer many other important questions which previously may have seemed unconnected, like “How do we automate calculations?”, “How do we reduce rounding errors when reconciling bank accounts?”, and “How do we represent highly precise measurements?”

Foundationality is both important and hard

Thinking clearly about how a question is framed is important because the framing affects how people attempt to answer it and the effect of those answers in the world. A more-foundational question will have higher-impact answers, often in unexpected and previously unconnected areas.

Unfortunately, it also takes more effort to push question framings toward greater foundationality. Getting to more foundational framings often requires identifying and suspending implicit assumptions about how things work (or, rather, how things “should” work). And foundational questions are often accused of being “too abstract” or “not concrete enough,” so there will always be social pressure against attempts to make questions more foundational.

But! though it is hard, it is important to push for foundationality when asking questions precisely because more foundational questions stimulate answers that unlock the answers to many other important questions. We enable breakthroughs when we spend the time and effort to figure out how to articulate questions in more foundational ways.

Which is why we’ve been spending so much time articulating what foundationality is for this AI conference.

Not-knowing as a foundational issue for AI?

Now, I am absolutely guilty of interpreting not-knowing and uncertainty as being relevant to almost any complex problem domain … and AI is a complex problem domain.

There are many extremely eminent people thinking about what direction/s AI efforts should take. As a not-eminent person, my own instinct — not, I should be clear, shared by the other conference organisers — is that a very foundational question for AI involves understanding how to explicitly distinguish between and represent various forms of not-knowing in ways that machines can work with.

This is important because it isn’t even common to observe clear distinctions being made between formal risk and true uncertainty, let alone clear distinctions being made between the different types of not-knowing that make up true uncertainty. Among many other things, this makes it hard for humans to explain what humans can do which machines cannot, and thus hard for humans to decide what constitute subjectively desirable outcomes of AI development and adoption.

I’m still thinking about how to frame this question properly, so what follows is not fully baked. My main assumption here is that an AI system cannot incorporate partial knowledge without humans having a way to represent it symbolically. Some other considerations:

Several types of partial knowledge are relevant to AI systems. Partial knowledge includes both numerically quantifiable formal risk and at least four types of numerically unquantifiable true uncertainty: not-knowing about possible actions and outcomes, not-knowing about causation, and not-knowing about the relative value of outcomes.

Each of these types of not-knowing is conceptually different from the others and affects how we think about decisionmaking differently. They affect how we think about bias, learning from limited data, interpretation of ambiguous situations, conceptions of expertise, evaluations of performance relative to human performance, and subjective desirability of outcomes — among many other important things.

Only formal risk is currently symbolically representable in ways (i.e., numerical probabilities) that an AI system can incorporate. This means AI systems either omit non-risk forms of not-knowing or conflate them (there are some examples here).

AI systems that omit and conflate these types of not-knowing become problematic to understand and interpret, and therefore problematic to deploy and use.

So, even provisionally, it seems that answering this question (“How can we explicitly distinguish between and symbolically represent different types of not-knowing in ways machines can work with?”) would make it easier to answer more self-evidently important questions, including (but probably not limited to),

“How do we design AI systems that are not biased (or only explicitly biased)?”

“How do we design AI systems that can learn from limited data?”

“How do we design AI systems that can interpret situations?”

“What types of work would AI systems be better at than humans?”

“What types of work should AI systems replace humans for?”

“How can we design safe AI systems given simultaneously diverse, changing, and contingent definitions of what ‘safety’ means?”

See you in a couple of weeks,

VT

foundationality is very similar to 'eigen vector' thinking and in the real world problem solving both could answer 70 to 80 plus percentage of the answer while the remaining answer requires little less foundationsal iterative questions to get to near 100 percent answer

Questions : Foundationality :: Answers : Elegance ? (Elegance as in https://stefanlesser.substack.com/i/85697655/elegance-multi-aptness)