Hello friends,

This issue highlights three essays I wrote a few years ago, on the connections between tradeoffs and strategy:

Why exploring tradeoffs makes it easier to relate productively to uncertainty.

Why clarifying tradeoffs makes it easier to adapt to uncertainty.

How articulating tradeoffs is a better way to set effective shared goals (than conventional strategic goal-setting exercises).

Now, here’s the context: I’ve been thinking a lot about tradeoffs in a practical-strategic way.

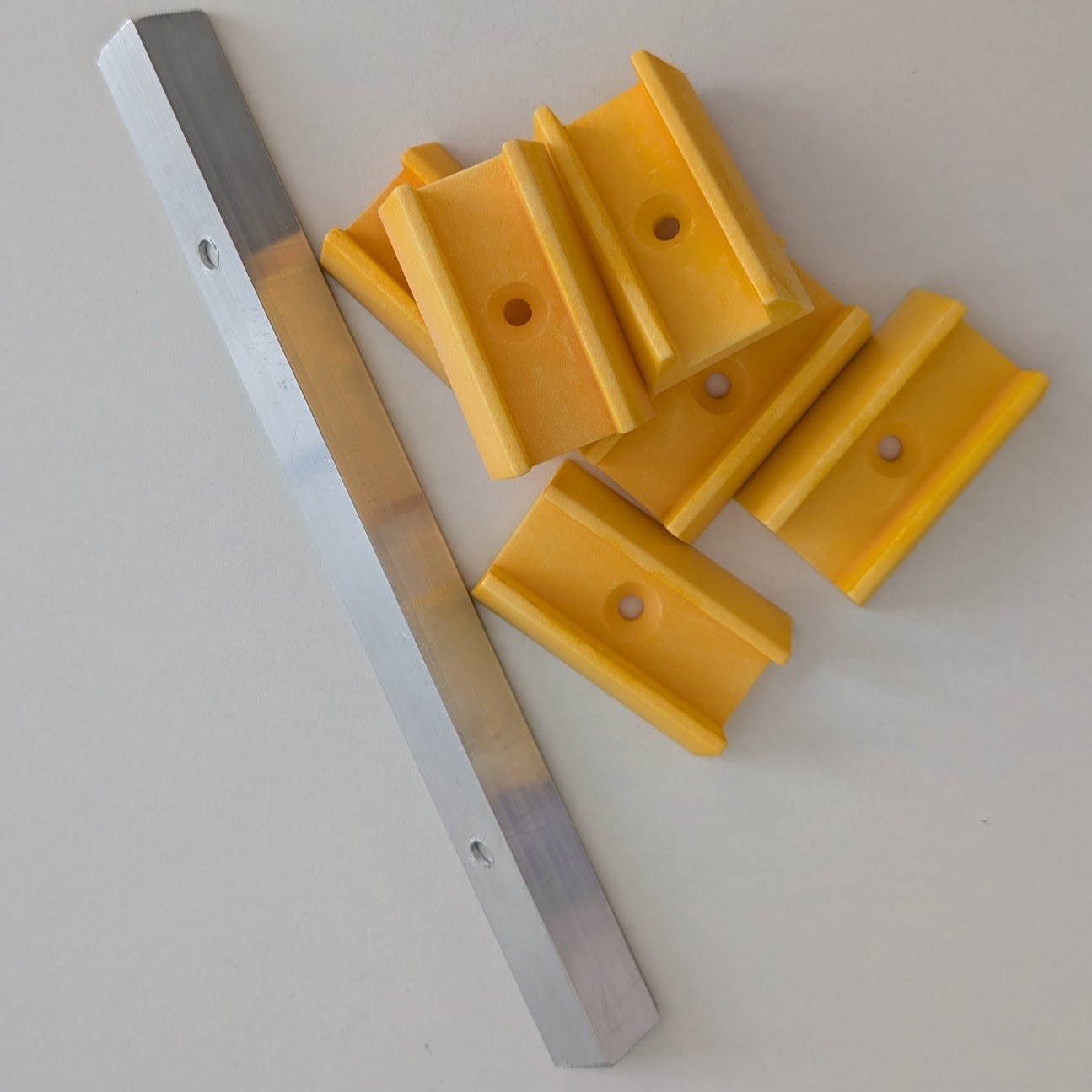

Many months ago, I reported that I’d accidentally fallen into a DIY rabbithole. I have still not emerged from it. For some weeks, in pockets of time snatched from doing Other Stuff, I’ve been gradually designing and fabricating hardware and components for 250ft² of built-in shelving, and fitting the shelves into two alcoves.

This process has been what Donald Schön calls a reflective conversation with the situation: “In a good process of design, [the] conversation with the situation is reflective. In answer to the situation’s back-talk, the designer reflects-in-action on the construction of the problem, the strategies of action, or the model of the phenomena, which have been implicit in his moves.”1

And there was so much back-talk from this particular situation, as these alcoves have not one single truly right angle or flat surface. (These built-in shelves are not the first time I have thought too much about furniture considerations.)

One way to fit a built-ins into an irregular space is to construct a perfectly regular, rectilinear shelving unit and install it with panels that conceal where the dimensions of the space differ from the dimensions of the unit. These panels hide (sort of) the fact that the unit “works” because it is designed to be insulated from the irregularities of the space it inhabits. This is both a way to build shelves and a metaphor for a way of dealing with a messy reality.

But this is not the only way.

For #reasons2, I prefer constructions that engage directly with their irregular environments. These types of constructions seldom achieve a high level of finish. But their particular virtue is that they are more likely to respond deeply to the realities of the spaces they occupy. (The latter is a characteristic of things worth keeping, and a common feature of structures made by “non-pedigreed” architects.)

In other words, there’s a tradeoff that usually needs to be made: Finish quality on the one hand, and responsiveness to reality on the other. Many people would choose finish quality over responsiveness to reality … and some would then feel subliminally discomfited for years by the wrongness of the perfectly rectilinear shelving unit in the slightly canted and off-square alcove by the entranceway.

For me, the subjectively desirable configuration of tradeoffs is to try and build shelving that is responsive to reality even at the expense of finish quality. This is both a way to build shelves and a metaphor for a way of dealing with a messy reality.

Preferring an unconventional configuration of tradeoffs can produce better — more enjoyable, more responsive, more novel — outcomes. And articulating acceptable and unacceptable configurations of tradeoffs can lead to more freedom to act.

See you next time,

VT

Unsurprisingly, the model of design as a reflective conversation with a situation has ramifications for thinking about artificial intelligence.

One of the reasons is that such constructions are usually brittle in a good way.

yeah. i had a carpenter quit on me because he was unwilling to "engage directly with their irregular environments"

and what of loose coupling? p/ex, shelves that, by virtue of an inner integrity call attention to the gappiness (ruggedness?) of the shelf-alcove interface without trying to change it — and in this way help us make peace with the fact that someday this arrangement (shelves, alcove) will change …